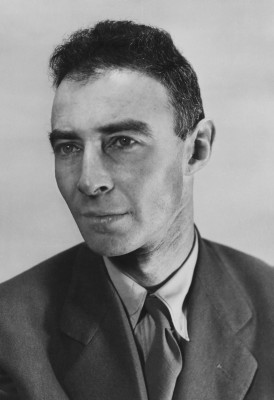

Age, Biography, and Wiki

Jimmy Hoffa was born on February 14, 1913, in Brazil, Indiana. His early life was marked by hardship after his father, a coal miner, died when Hoffa was just seven years old. His family moved to Detroit in 1924, where Hoffa began working at a young age. He became involved in union activities in the 1930s and quickly rose through the ranks of the Teamsters, becoming president in 1957.

| Occupation | Presidents |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 14 February 1913 |

| Age | 112 Years |

| Birth Place | Brazil, Indiana, U.S. |

| Horoscope | Aquarius |

| Country | Brazil |

Height, Weight & Measurements

Unfortunately, detailed information about Jimmy Hoffa's height and weight is not readily available in the public domain.

Hoffa married Josephine Poszywak, an 18-year-old Detroit laundry worker of Polish heritage, in Bowling Green, Ohio, on September 25, 1936. The couple had met six months earlier during a non-unionized laundry workers' strike action; Hoffa described the meeting as feeling as though he had been "hit on the chest with a blackjack". They had two children: a daughter, Barbara Ann Crancer, and a son, James P. Hoffa. The Hoffas paid $6,800 in 1939 for a modest home in northwestern Detroit. The family later owned a simple summer lakefront cottage in Orion Township, Michigan, north of Detroit.

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Jimmy Hoffa was married to Josephine Poszywak, and they had two children together, Barbara Crancer and James P. Hoffa. There is no significant information available about any other romantic relationships.

The doctor who delivered him thought Hoffa's mother had a tumor, not a baby, in her abdomen, so he was initially referred to as “The Tumor.” His father, who was of German descent from what is now referred to as the Pennsylvania Dutch, died in 1920 from lung disease when Hoffa was seven years old. His mother was of Irish ancestry. The family moved to Detroit in 1924, where Hoffa was raised and lived for the rest of his life. He left school at the age of 14 and began working full-time manual labor jobs to help support his family.

Between 2:15 and 2:30 p.m., an annoyed Hoffa called his wife from a payphone on a post in front of Damman Hardware, directly behind the Machus Red Fox, and complained that Giacalone had not shown up and that he had been stood up. His wife told him she had not heard from anyone. He told her he would be home in Lake Orion by 4:00 p.m. to grill steaks for dinner. Several witnesses saw Hoffa standing by his car and pacing the restaurant's parking lot. Two men saw Hoffa, recognized him, and stopped to chat with him briefly and to shake his hand. Hoffa also made a call to Linteau in which he again complained that the men were late. Linteau gave the time as 3:30 p.m., but the FBI suspected that it was earlier, based on the timing of other phone calls from Linteau's office from around that time. The FBI estimates that Hoffa left the location without a struggle around 2:45–2:50 p.m. One witness reported seeing Hoffa in the back of a maroon "Lincoln or Mercury" car with three other people.

At 7 a.m. the next day, Hoffa's wife called her son and daughter to say that their father had not come home. At 7:20 a.m., Linteau went to the Machus Red Fox and found Hoffa's unlocked car in the parking lot, but there was no sign of Hoffa, nor any indication of what had happened to him. Linteau called the police, who later arrived at the scene. The Michigan State Police were brought in, and the FBI was alerted. At 6 p.m., Hoffa's son, James, filed a missing person report. The Hoffa family offered a $200,000 reward for any information about his disappearance.

After years of investigation involving numerous law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, officials have not reached a definitive conclusion as to Hoffa's fate or who was involved. Hoffa's wife, Josephine, died on September 12, 1980, and is interred at White Chapel Memorial Cemetery in Troy, Michigan. On December 9, 1982, Hoffa was declared legally dead as of July 30, 1982, by Oakland County, Michigan Probate Judge Norman R. Barnard.

| Parents | |

| Husband | Josephine Poszywak (m. 1936) |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

Estimating Jimmy Hoffa's net worth is challenging due to the lack of financial records. However, his influence and power within the labor union likely afforded him a comfortable lifestyle. His salary as president of the Teamsters was substantial, but exact figures are not publicly disclosed. Hoffa's association with organized crime figures also contributed to speculation about his financial dealings.

Career, Business, and Investments

Hoffa's career as a labor leader was marked by significant achievements. He centralized administration and bargaining within the Teamsters, leading to the creation of the first national freight-hauling agreement. Under his leadership, the union grew to become the largest in the United States. Hoffa's efforts in organizing and negotiating contracts led to substantial wage increases and improved working conditions for union members.

Hoffa began union organizational work at the grassroots level as a teenager through his job with a grocery chain, which paid substandard wages and offered poor working conditions with minimal job security. The workers were displeased with that situation and tried to organize a union to better their wages. Although Hoffa was young, his courage and approachability in that role impressed fellow workers, and he rose to a leadership position. By 1932, after refusing to work for an abusive shift foreman, Hoffa left the grocery chain, partly because of his union activities. He was then invited to become an organizer with Local 299 of the Teamsters in Detroit. Between 1933 and 1935, Hoffa organized by pulling up at the side of the road alongside sleeping truck drivers, waking them up, and giving them his sales pitch.

The Teamsters organized truck drivers and warehousemen throughout the Midwest and then nationwide. Hoffa played a major role in the union's skillful use of "quickie strikes," secondary boycotts, and other means of leveraging union strength at one company, moves to organize workers at another, and finally to win contract demands at other companies. That process, which took several years starting in the early 1930s, eventually brought the Teamsters to a position of being one of the most powerful unions in the United States.

Hoffa worked to defend the Teamsters from raids by other unions, including the Congress of Industrial Organizations, and he extended the Teamsters' influence in the Midwest from the late 1930s to the late 1940s. Hoffa obtained a deferment from military service in World War II by successfully making a case for his union leadership skills being of more value to the nation by keeping freight running smoothly to assist the war effort. Although he never actually worked as a truck driver, he became president of Local 299 in December 1946. He then rose to lead the combined group of Detroit-area locals shortly afterwards and later advanced to become head of the Michigan Teamsters groups.

The IBT moved its headquarters from Indianapolis to Washington, DC, taking over a large office building in the capital in 1955. IBT staff was also enlarged, with many lawyers hired to assist with contract negotiations. Following his 1952 election as vice-president, Hoffa began spending more of his time away from Detroit, either in Washington or traveling around the country for his expanded responsibilities. Hoffa's personal lawyer was Bill Bufalino.

When Hoffa entered prison, Frank Fitzsimmons was named acting president of the union, and Hoffa planned to run the union from prison through Fitzsimmons. Fitzsimmons was a Hoffa loyalist, fellow Detroit resident, and a longtime member of Teamsters Local 299, who owed his own high position in large part to Hoffa's influence. Despite this, Fitzsimmons soon distanced himself from Hoffa's influence and control after 1967, to Hoffa's displeasure. Fitzsimmons also decentralized power somewhat within the IBT's administration structure, forgoing much of the control Hoffa took advantage of as union president. While still in prison, Hoffa resigned as Teamsters president on June 19, 1971, and Fitzsimmons was elected Teamsters president on July 9, 1971.

Provenzano, once an ally of Hoffa, became an enemy after having a reported feud when both were in federal prison at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania in the 1960s. In 1973 and 1974, Hoffa asked him for his support to regain his former position, but Provenzano refused and threatened Hoffa by reportedly saying he would pull out his guts or kidnap his grandchildren.

Social Network

In the era of Jimmy Hoffa, social media did not exist. However, his influence extended through his leadership and public presence, which garnered significant media attention during his time.

In 1952, a petty criminal living in New York, Marvin Elkind, was assigned by gangster Anthony Salerno to work as Hoffa's chauffeur. In a 2008 interview, Elkind said of his four years working as a chauffeur: "Mr. Hoffa was a tremendously intimidating man. This man had no fear at all, of nothing, showed very little emotion, had completely no sense of humour, and was dedicated to the people that belonged to his union. When you drive these people you learn a lot and I’ll tell you why. They don’t know you’re there. You become a piece of the car, just like an extra gear shift or a brake, and they talk."

Hoffa faced immense resistance to his re-establishment of power from many corners and had lost much of his earlier support even in the Detroit area. As a result, he intended to begin his comeback at the local level with Local 299 in Detroit, where he retained some influence. In 1975, Hoffa was working on an autobiography, Hoffa: The Real Story, which was published a few months after his disappearance. He had earlier published a book titled The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (1970).

Piersante suggested that the killing was accidental, and that the men who were sent to meet Hoffa were only meant to be "insultingly low-level messengers". He argued that Hoffa had no realistic prospects for a comeback, that the disappearance did not share the usual characteristics of a Mafia hit and that it risked encouraging action against organized crime (as indeed happened). This theory did not gain wide acceptance among criminologists.

It is theorized that O'Brien picked Hoffa up from the Machus Red Fox parking lot, and Hoffa was either killed in the car or driven to an unspecified location to be killed. Keith Corbett, a former US Prosecuting Attorney, has since suggested that O'Brien would have been considered too unreliable to be entrusted with a role in such a high-profile murder. He instead suggested that Vito "Billy" Giacalone was the familiar figure.

In the book I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran and the Closing of the Case on Jimmy Hoffa (2004), author Charles Brandt writes that Frank Sheeran, an alleged professional killer for the mob and a longtime friend of Hoffa, confessed to killing him. According to the book, Sheeran claims O'Brien drove him, Hoffa, and fellow mobster Sal Briguglio to a house in Detroit. The house belonged to an elderly widow who was lured out of her house, making the alleged murder scene an implausible location for law enforcement to suspect. Once at the location, Sheeran claims he shot Hoffa dead. Sheeran then claimed Hoffa's body was taken to a crematorium in another state and cremated. Further evidence refutes Sheeran's claims. The truthfulness of the book, including Sheeran's confessions to killing Hoffa, has been disputed by "The Lies of the Irishman", an article in Slate by Bill Tonelli, and "Jimmy Hoffa and 'The Irishman': A True Crime Story?" by Harvard Law School Professor Jack Goldsmith, which appeared in The New York Review of Books. Buccellato doubts that the Mafia would have entrusted an Irish American with this role and also believes that Hoffa would have refused to travel that far from the restaurant.

In the comedy film Bruce Almighty (2003), the titular character uses powers endowed by God to manifest Hoffa's body in order to procure a story interesting enough to reclaim his career in the news industry.

* I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran and the Inside Story of the Mafia, the Teamsters, and the Last Ride of Jimmy Hoffa [Paperback], by Charles Brandt

Education

Jimmy Hoffa dropped out of school at the age of 14 to work and support his family. His education was largely experiential, gained through his involvement in labor union activities.

Jimmy Hoffa's impact on the labor movement and his mysterious disappearance have made him a figure of enduring interest in American history. Despite the lack of precise financial information, his legacy as a powerful labor leader remains unquestioned.

From an early age, Hoffa was a union activist: he became an important regional figure with the IBT by his mid-20s. By 1952, he was the national vice-president of the IBT and between 1957 and 1971, he served as its general president. Hoffa secured the first national agreement for teamsters' rates in 1964 with the National Master Freight Agreement. He played a major role in the growth and the development of the union, which eventually became the largest by membership in the United States, with over 2.3 million members at its peak, during his terms as its leader.

Following his re-election as president in 1961, Hoffa worked to expand the union. In 1964, he succeeded in bringing virtually all over-the-road truck drivers in North America under a single National Master Freight Agreement, which may have been his biggest achievement in a lifetime of union activity. Hoffa then tried to bring airline workers and other transport employees into the union, with limited success. He then faced immense personal strain as he was under investigation, on trial, launching appeals of convictions, or imprisoned for virtually all of the 1960s.

In discussing potential motives, both the 1976 Hoffex Memo and scholarship prior to its release focus on Mafia opposition to Hoffa's plans to regain the Teamsters' leadership and the threat Hoffa posed to the Mafia's control over the union's pension fund. The Hoffex Memo noted that Provenzano was not senior enough to order a Mafia hit, though it did not rule out the possibility that his or someone else's personal vendetta against Hoffa was a motive. Scott Burnstein, a crime historian and journalist, argued in 2019 that Provenzano's role in the entire case was limited to acting as a lure.

The location of the murder is also unknown, but any violence in the restaurant parking lot would have easily attracted witnesses. Therefore, the Hoffex Memo suspects Hoffa was lured away to a different murder location. James Buccellato, a professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern Arizona University, suggested in 2017 that it was likely that Hoffa was murdered one mile away from the restaurant at the house of Carlo Licata, the son of the mobster Nick Licata.

In 2012, Roseville, Michigan, police took samples from the ground under a suburban Detroit driveway after a person reported having witnessed the burial of a body there around the time of Hoffa's 1975 disappearance. Tests by Michigan State University anthropologists found no evidence of human remains.

* Out of the Jungle: Jimmy Hoffa and the Remaking of the American Working Class, by Thaddeus Russell, 2001, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, ISBN 0-375-41157-7.

* Guide to James R. Hoffa Documentation Collection, 1954–1976, Special Collections Research Center, Estelle and Melvin Gelman Library, The George Washington University