Age, Biography, and Wiki

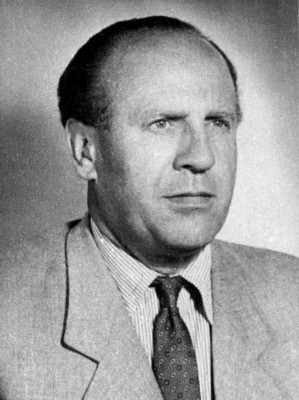

Oskar Schindler was born on April 28, 1908, in Zwittau, Moravia, which is now part of the Czech Republic. He gained international recognition for his heroic actions during World War II, despite being a member of the Nazi Party. Schindler's life was immortalized in the film "Schindler's List," directed by Steven Spielberg.

| Occupation | Business |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 28 April 1908 |

| Age | 117 Years |

| Birth Place | Zwittau, Margraviate of Moravia, Austria-Hungary |

| Horoscope | Taurus |

| Country | Austria |

| Date of death | 9 October, 1974 |

| Died Place | Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, West Germany |

Height, Weight & Measurements

There is limited information available regarding Oskar Schindler's physical attributes such as height and weight. However, his stature as a historical figure is well-documented.

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Schindler was married to Emilie Pelzl. After moving to Argentina, where they experienced financial difficulties, Schindler returned to Germany alone in 1957. Although he separated from his wife, they did not officially divorce.

Schindler moved to West Germany after the war, where he was supported financially by Jewish relief organisations. After receiving a partial reimbursement for his wartime expenses, he moved with his wife, Emilie, to Argentina, where they took up farming. When they went bankrupt in 1958 Schindler left his wife and returned to Germany, where he failed at several business ventures and relied on financial support from Schindlerjuden ("Schindler Jews")—the people whose lives he had saved during the war. He died on 9 October 1974 in Hildesheim, Germany, and was buried in Jerusalem on Mount Zion, the only former member of the Nazi Party to be honoured in this way. Oskar and Emilie Schindler were named Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1993.

His father was Johann "Hans" Schindler, the owner of a farm machinery business, and his mother was Franziska "Fanny" Schindler (née Luser). After attending primary and secondary school, Schindler enrolled in a technical school, from which he was expelled in 1924 for forging his report card. He later graduated but did not take the abitur exams that would have enabled him to go to university. Instead, he took courses in Brno in several trades, including chauffeuring and machinery, and worked for his father for three years. A motorcycle enthusiast since his youth, he bought a 250-cc Moto Guzzi racing motorcycle and competed recreationally in mountain races for the next few years.

On 6 March 1928 Schindler married Emilie Pelzl, daughter of a prosperous Sudeten German farmer from Maletein. They moved in with Oskar's parents and occupied the upstairs rooms, where they lived for seven years. Soon after marriage, Schindler quit working for his father and took a series of jobs, including a position at Moravian Electrotechnic and the management of a driving school. After an 18-month stint in the Czech army, where he rose to the rank of lance corporal in the Tenth Infantry Regiment of the 31st Army, he returned to Moravian Electrotechnic, which went bankrupt shortly afterward. His father's farm machinery business closed around the same time, leaving Schindler unemployed for a year. He took a job with Jaroslav Šimek Bank of Prague in 1931, where he worked until 1938.

Schindler was arrested several times in 1931 and 1932 for public drunkenness. Also around this time, he had an affair with Aurelie Schlegel, a school friend. They had a daughter, Emily, in 1933, and a son, Oskar Jr, in 1935. Schindler later claimed the boy was not his son. Schindler's father, an alcoholic, abandoned his wife in 1935. She died a few months later after a long illness.

After some time off to recover in Zwittau, Schindler was promoted to second in command of his Abwehr unit and relocated with his wife to Ostrava (Ostrau), on the Czech-Polish border, in January 1939. He was involved in espionage in the months leading up to Hitler's seizure of the remainder of Czechoslovakia in March. Emilie helped him with paperwork, processing and hiding secret documents in their apartment for the Abwehr office. As Schindler frequently travelled to Poland on business, he and his 25 agents were in a position to collect information about Polish military activities and railways for the planned invasion of Poland. One assignment called for his unit to monitor and provide information about the railway line and tunnel in the Jablunkov Pass, deemed critical for the movement of German troops. Schindler continued to work for the Abwehr until as late as fall 1940, when he was sent to Turkey to investigate corruption among the Abwehr officers assigned to the German embassy there.

In addition to workers, Schindler moved 250 wagonloads of machinery and raw materials to the new factory. Few if any useful artillery shells were produced at the plant. When officials from the Armaments Ministry questioned the factory's low output, Schindler bought finished goods on the black market and resold them as his own. The rations provided by the SS were insufficient to meet the workers' needs, so Schindler spent most of his time in Kraków obtaining food, armaments, and other materials. His wife Emilie remained in Brünnlitz, surreptitiously obtaining additional rations and caring for the workers' health and other basic needs.

To escape capture by the Soviets, Schindler and his wife departed westward in their vehicle, a two-seater Horch, initially with several fleeing German soldiers riding on the running boards. A truck containing Schindler's mistress Marta, several Jewish workers, and a load of black market trade goods followed. Soviet troops confiscated the Horch at the city of České Budějovice, which the Soviets had already captured. The Schindlers were unable to recover a diamond Oskar had hidden under the seat. They continued by train and on foot until they reached the American lines at Lenora and then travelled to Passau, where an American Jewish officer arranged for them to travel to Switzerland by train. They moved to Bavaria in Germany in late 1945.

In 1949 Schindler emigrated to Argentina, where he tried raising chickens and then nutria (coypu), a small animal raised for its fur. When the business went bankrupt in 1958, he left his wife and returned to Germany, where he had a series of unsuccessful business ventures, including a cement factory. He declared bankruptcy in 1963 and suffered a heart attack the next year, which led to a monthlong hospital stay. Remaining in contact with many of the Jews he had met during the war, including Stern and Pfefferberg, Schindler survived on donations sent by Schindlerjuden from all over the world.

For his work during the war, on 8 May 1962 Yad Vashem invited Schindler to a ceremony in which a carob tree was planted in his honour on the Avenue of the Righteous. Schindler received awards for his efforts, including the German Order of Merit in 1966. Schindler died of liver failure on 9 October 1974. He is buried in Jerusalem on Mount Zion, possibly the only member of the Nazi Party to be honoured in this way. On 24 June 1993 he and his wife were named Righteous Among the Nations, an award the State of Israel bestows on non-Jews who took an active role in rescuing Jews during the Holocaust. Schindler, along with Karl Plagge, Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, Helmut Kleinicke, and Hans Walz are among the few Nazi Party members to be given this award.

| Parents | |

| Husband | Emilie Pelzl (m. 1928) |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

Oskar Schindler's net worth during his lifetime was significantly impacted by his wartime efforts. He spent his entire fortune on bribes and supplies to protect his workers, leaving him financially strained after the war. His financial situation was supported by Jewish relief organizations and later by the people he had saved, known as "Schindlerjuden".

Career, Business, and Investments

Schindler's career as an industrialist was marked by his ownership of the enamelware factory in Kraków, Poland. He leveraged his connections with Nazi officials to save thousands of lives by employing them in his factory. Post-war, he attempted several business ventures but was unsuccessful.

Schindler grew up in Zwittau, Moravia, and worked in several trades until he joined the Abwehr, the military intelligence service of Nazi Germany, in 1936. Before the beginning of the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1938, he collected information on railways and troop movements for the German government. He was arrested for espionage by the Czechoslovak government but was released under the terms of the Munich Agreement that year. He continued to collect information for the Nazis, working in Poland in 1939 before the invasion of Poland at the start of the Second World War. He joined the Nazi Party in 1939. In 1939 he acquired an enamelware factory in Kraków, Poland, which employed at its peak in 1944 about 1,750 workers, of whom 1,000 were Jews. His Abwehr connections helped him protect his Jewish workers from deportation and death in the Nazi concentration camps. As time went on, he had to give Nazi officials ever larger bribes and gifts of luxury items obtainable only on the black market to keep his workers safe.

Schindler first arrived in Kraków (Krakau) in October 1939 on Abwehr business and took an apartment the following month. Emilie maintained the apartment in Ostrava and visited Oskar in Kraków at least once a week. In November 1939, he contacted interior decorator Mila Pfefferberg to decorate his new apartment. Her son, Leopold "Poldek" Pfefferberg, soon became one of his contacts for black market trading. They eventually became lifelong friends.

The same month, Schindler was introduced to Itzhak Stern, an accountant for Schindler's fellow Abwehr agent Josef "Sepp" Aue, who had taken over Stern's formerly-Jewish-owned place of employment as a treuhänder (trustee). Property belonging to Polish Jews, including their possessions, places of business, and homes, were seized by the Germans beginning immediately after the invasion, and Jewish citizens were stripped of their civil rights. Schindler showed Stern the balance sheet of a company he was thinking of acquiring, an enamelware factory called Rekord Ltd owned by a consortium of Jewish businessmen that had filed for bankruptcy earlier that year. Stern advised him that rather than running the company as a trusteeship under the auspices of the Haupttreuhandstelle Ost (Main Trustee Office for the East), he should buy or lease the business, as that would give him more freedom from the Nazis' dictates, including freedom to hire more Jews.

With the financial backing of several Jewish investors, including one of the owners, Abraham Bankier, Schindler signed an informal lease agreement on the factory on 13 November 1939 and formalised the arrangement on 15 January 1940. He renamed it Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik (German Enamelware Factory) or DEF, and it soon became known by the nickname "Emalia". He initially acquired a staff of seven Jewish workers (including Bankier, who helped him manage the company) and 250 non-Jewish Poles. At its peak in 1944, the business employed around 1,750 workers, a thousand of whom were Jews. Schindler also helped run Schlomo Wiener Ltd, a wholesale outfit that sold his enamelware, and was leaseholder of Prokosziner Glashütte, a glass factory.

Initially, Schindler was mostly interested in the business's money-making potential and hired Jews because they were cheaper than Poles—the wages were set by the occupying Nazi regime. Later he began shielding his workers without regard for cost. The status of his factory as a business essential to the war effort became a decisive factor in enabling him to protect his Jewish workers. Whenever Schindlerjuden (Schindler Jews) were threatened with deportation, he claimed exemptions for them. He claimed wives, children, and even people with disabilities were necessary mechanics and metalworkers. On one occasion, the Gestapo came to Schindler demanding that he hand over a family that possessed forged identity papers. "Three hours after they walked in," Schindler said, "two drunk Gestapo men reeled out of my office without their prisoners and without the incriminating documents they had demanded."

In 1943 Schindler was contacted by Zionist leaders in Budapest via members of the Jewish resistance movement. He travelled to Budapest several times to report in person on Nazi mistreatment of the Jews. He brought back funding provided by the Jewish Agency for Palestine and turned it over to the Jewish underground.

Social Network

In today's context, Schindler did not have a "social network" as we understand it now, but his legacy lives on through historical accounts and films like "Schindler's List." His story has inspired countless people worldwide.

In 1980 the Australian author Thomas Keneally by chance visited Pfefferberg's luggage store in Beverly Hills, California, while en route home from a film festival in Europe, and Pfefferberg told him Schindler's story. He gave Keneally copies of some materials he had on file, and Keneally decided to make a fictionalised treatment of the story. After extensive research and interviews with surviving Schindlerjuden, he wrote his historical novel Schindler's Ark (published in the United States as Schindler's List), which was released in 1982.

Other film treatments include a 1983 British television documentary produced by Jon Blair for Thames Television, Schindler: His Story as Told by the Actual People He Saved (released in the US in 1994 as Schindler: The Real Story), and a 1998 A&E Biography special, Oskar Schindler: The Man Behind the List.

In early April 2009, a carbon copy of one version of the list was discovered at the State Library of New South Wales by workers combing through boxes of materials collected by Keneally. The 13-page document, yellow and fragile, was filed among research notes and original newspaper clippings. The document was given to Keneally in 1980 by Pfefferberg when he was persuading him to write Schindler's story. This version of the list contains 801 names and is dated 18 April 1945; Pfefferberg is listed as worker number 173. Several authentic versions of the list exist, because the names were retyped several times as conditions changed in the hectic days at the end of the war. One of four existing copies of the list was offered at a ten-day auction starting on 19 July 2013 on eBay at a reserve price of US$3 million. It received no bids.

Education

Details about Oskar Schindler's formal education are not widely documented. However, his resourcefulness and ability to navigate complex political situations were crucial to his success in saving lives during the Holocaust.

After the liquidation of the Płaszów camp, the Schindlerjuden decided to give Schindler a memento. The original investors in the enamel factory canvassed the workers for ideas. Knowing there were several jewelers among their group, a man named Simon Yeret, formerly a prosperous timber merchant, offered a gold bridge from his own mouth. The bridge was removed and its metal melted with a few scavenged silver coins. A jeweller named Jozef Gross cut a section of lead pipe and created a master signet ring out of which the gold version would be cast. Gross shaved two cuttlebones flat and squeezed the lead master between them until an impression had been pressed into the mould. This was filled with the gold from Yeret's bridge. Gross then filed and polished the gold ring. He engraved a paraphrase from the Talmud in Hebrew on the ring that said, "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire." Despite his mixed feelings about Schindler's character, Gross kept the cuttlebone mold and lead master for the rest of his life. They are currently housed at the Melbourne Holocaust Museum. The whereabouts of the actual ring have long been unknown, nor is it clear what Schindler did with it after the war.