Age, Biography, and Wiki

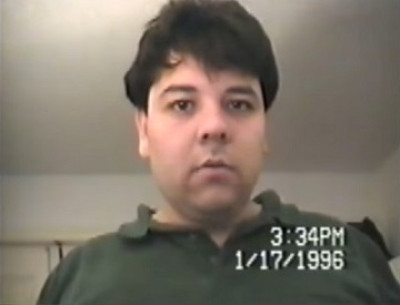

Robert Philip Hanssen was born on April 18, 1944, and passed away on June 5, 2023. He was a prominent figure in the FBI, serving as a counterintelligence agent from 1976 until his arrest in 2001. Hanssen's espionage activities began as early as 1979, although they were not fully exposed until much later. His Wikipedia page provides detailed insights into his life and career: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hanssen.

| Occupation | Criminals |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 18 April 1944 |

| Age | 81 Years |

| Birth Place | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Horoscope | Aries |

| Country | U.S |

Height, Weight & Measurements

There is limited public information available about Hanssen's physical measurements.

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Hanssen was married and had six children. His family life was generally private, and little is known about his relationship dynamics outside of his immediate family.

His father, Howard (died 1993), a Chicago police officer, was allegedly emotionally abusive to Hanssen during his childhood. Hanssen graduated from William Howard Taft High School in 1962 and attended Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, where he earned a bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1966.

In 1990, Hanssen's brother-in-law, Mark Wauck, who was also an FBI employee, recommended to the FBI that Hanssen be investigated for espionage because his sister, Hanssen's wife, told him that her sister, Jeanne Beglis, had found a pile of cash on a dresser in the Hanssens' house. Bonnie had previously told her brother that Hanssen once talked about retiring in Poland, then part of the Eastern Bloc. Wauck also knew that the FBI was hunting for a mole and spoke with his supervisor, who took no action.

By 1998, using FBI criminal profiling techniques, the pursuers suspected an innocent man: Brian Kelley, a CIA operative involved in the Bloch investigation. The CIA and FBI searched his house, tapped his telephone, and surveilled him, following him and his family everywhere. In November 1998, they had a man with a foreign accent come to Kelley's door, warn him that the FBI knew he was a spy, and tell him to show up at a Metro station the next day to escape. Kelley instead reported the incident to the FBI. In 1999, the FBI even interrogated Kelley, his ex-wife, two sisters, and three children. All denied everything. He was eventually placed on administrative leave, where he remained, falsely accused until after Hanssen was arrested.

Represented by Washington, D.C., lawyer Plato Cacheris, Hanssen negotiated a plea bargain that enabled him to avoid the death penalty in exchange for cooperating with authorities. On July 6, 2001, he pleaded guilty to 13 counts of espionage, one count of attempted espionage, and one of conspiracy to commit espionage in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. On May 10, 2002, Hanssen was sentenced to 15 consecutive sentences of life in prison without the possibility of parole. "I apologize for my behavior. I am shamed by it," Hanssen told U.S. District Judge Claude Hilton. "I have opened the door for calumny against my totally innocent wife and children. I have hurt so many deeply." Hanssen was Federal Bureau of Prisons prisoner #48551-083. From July 17, 2002, until his death, he served his sentence at the ADX Florence, a federal supermax prison near Florence, Colorado, in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day.

According to USA Today, those who knew the Hanssens described them as a close family. They attended Mass weekly and were very active in Opus Dei. Hanssen's three sons attended The Heights School in Potomac, Maryland, an all-boys preparatory school. His three daughters attended Oakcrest School for Girls in Vienna, Virginia, an independent Roman Catholic school. Both schools are associated with Opus Dei. Hanssen's wife, Bonnie, retired from teaching theology at Oakcrest in 2020.

At Hanssen's suggestion, and without his wife's knowledge, a friend named Jack Hoschouer, a retired Army officer, would sometimes watch the Hanssens having sex through a bedroom window. Hanssen then began to videotape his sexual encounters secretly and shared the videotapes with Hoschouer. Later, he hid a video camera in the bedroom connected via a closed-circuit television line so that Hoschouer could observe the Hanssens from the Hanssens' guest bedroom. He also explicitly described the sexual details of his marriage in Internet chat rooms, giving information sufficient for those who knew them to recognize the couple.

| Parents | |

| Husband | Bernadette "Bonnie" Wauck (m. 1968-2023) |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

Hanssen's net worth at the time of his arrest was estimated to be around $1.4 million, which he earned through his espionage activities. He received this amount in cash, diamonds, and bank deposits from his Russian handlers over a period of about 15 years. His salary as an FBI agent was not publicly disclosed, but it was not significant compared to the earnings from his espionage.

Career, Business, and Investments

Hanssen's career in the FBI spanned over two decades, during which he held various positions, including roles in counterintelligence. His assignments provided him access to sensitive information, which he exploited for espionage purposes. He did not have any notable business investments or ventures outside of his espionage activities.

Hanssen applied for a cryptography job at the National Security Agency following his college graduation but was turned down due to budget constraints. He enrolled in dental school at Northwestern University, but he switched his focus to business after three years. Hanssen received an MBA in accounting and information systems in 1971 and took a job with an accounting firm. He quit after one year and joined the Chicago Police Department as an internal affairs investigator, specializing in forensic accounting. In January 1976, Hanssen left the Chicago police to join the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

In 1981, Hanssen was transferred to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., and relocated his family to the suburb of Vienna, Virginia. His new job in the FBI's budget office gave him access to information involving many different FBI operations. This included all the FBI activities related to wiretapping and electronic surveillance, which were Hanssen's responsibility. He became known in the FBI as an expert on computers.

Three years later, Hanssen transferred to the FBI's Soviet analytical unit, responsible for studying, identifying, and capturing Soviet spies and intelligence operatives in the United States. Hanssen's section evaluated Soviet agents who volunteered to give intelligence to determine whether they were genuine or re-doubled agents. In 1985, Hanssen was again transferred to the FBI's field office in New York City, where he continued to work in counterintelligence against the Soviets. After the transfer, while on a business visit back to Washington, he resumed his espionage career.

During the same period, Hanssen searched the FBI's internal computer case record to see if he was being investigated. He was indiscreet enough to type his name into FBI search engines. Finding nothing, Hanssen decided to resume his spy career after eight years without contact with the Russians. He established contact with the SVR (a successor to the Soviet-era KGB) during the autumn of 1999. He continued to perform incriminating searches of FBI files for his name and address.

The FBI surveilled Hanssen and soon discovered he was again in contact with the Russians. To bring him back to FBI headquarters, where he could be closely monitored and kept away from sensitive data, they promoted him. They gave him a new job supervising FBI computer security. Hanssen was given an office and an assistant, Eric O'Neill, who was actually a young FBI surveillance specialist who had been assigned to watch Hanssen. O'Neill ascertained that Hanssen was using a Palm III PDA to store his information. When O'Neill was able to briefly obtain Hanssen's PDA and have agents download and decode its encrypted contents, the FBI acquired their conclusive evidence.

During his final days with the FBI, Hanssen began to suspect something was wrong. In early February 2001, he asked his friend at a computer technology company for a job. He also believed he heard noises on his car radio that indicated it was bugged, although the FBI was later unable to reproduce the noises Hanssen claimed to have heard. In the last letter he wrote to the Russians, which was found by the FBI when he was arrested, Hanssen said that he had been promoted to a "do-nothing job ... outside of regular access to information" and that "Something has aroused the sleeping tiger".

Social Network

Hanssen did not have a public social media presence, as his activities were clandestine and not publicly disclosed during his lifetime.

Hanssen continued to take risks in 1993 when he hacked into the computer of a fellow FBI agent, Ray Mislock, printed out a classified document from Mislock's computer and took the document to Mislock, saying, "You didn't believe me that the system was insecure." Hanssen's superiors were not amused and began an investigation. In the end, officials believed his claim that he was merely demonstrating flaws in the FBI's security system. Mislock has since theorized that Hanssen probably went onto his computer to see if his superiors were investigating him for espionage and invented the document story to cover his tracks.

IT personnel from the National Security Division's (NSD) Internet Information Services (IIS) Unit were sent to investigate Hanssen's desktop computer after a reported failure. NSD chief Johnnie Sullivan ordered the computer impounded after it seemed to have been tampered with. A digital investigation found that an attempted hacking had occurred using a password cracking program installed by Hanssen, which caused a security alert and lockup. After confirmation by the FBI Computer Analysis Response Team (CART) Unit, Sullivan filed a report with the Office of Professional Responsibility requesting the further investigation of Hanssen's attempted hack. Hanssen claimed he was trying to connect a color printer to his computer but needed the password cracker to bypass the administrative password. The FBI believed his story, and Hanssen was merely given a warning.

Despite these efforts at caution and security, Hanssen was sometimes reckless. He once said in a letter to the KGB that it should emulate the management style of Mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley—a comment that easily could have led an investigator to look at people from Chicago. Hanssen took the risk of recommending to his handlers that they try to recruit his closest friend, a colonel in the United States Army.

The Hanssen spy case was told in David Wise's book Spy: The Inside Story of How the FBI's Robert Hanssen Betrayed America, published by Random House in 2002. The investigation was further covered in Eric O'Neill's memoir Gray Day: My Undercover Mission to Expose America's First Cyber Spy, published by Penguin Random House in the spring of 2019.

Hanssen was the subject of a 2002 made-for-television movie, Master Spy: The Robert Hanssen Story, with a teleplay by Norman Mailer and starring William Hurt as Hanssen. Hanssen's jailers allowed him to watch the movie, but he was so angered by it that he turned it off. O'Neill's role in the capture of Robert Hanssen was dramatized in the 2007 movie Breach, in which Chris Cooper played the role of Hanssen and Ryan Phillippe played O'Neill. The 2007 documentary Superspy: The Man Who Betrayed the West describes the hunt to trap Hanssen.

Hanssen was mentioned in chapter 5 of Dan Brown's book The Da Vinci Code as the most noted Opus Dei member to non-members. His sexual deviancy and espionage conviction hurt the organization's reputation. The U.S. Court TV (now TruTV) television series Mugshots released an episode on the Robert Hanssen case titled "Robert Hanssen – Hanssen and the KGB". Ronald Kessler's book The Secrets of the FBI, briefly covers the case in chapter 15, "Catching Hanssen", chapter 16, "Breach", and chapter 17, "Unexplained Cash", based in part on interviews with Michael Rochford, who directed the FBI team that located the former KGB source that pointed to Hanssen after Rochford initially wrongly assumed CIA officer Brian Kelley was the master spy. Hanssen's story was featured in episode 4, under the name of "Perfect Traitor", of Smithsonian Channel's series Spy Wars, which aired at the end of 2019 and was narrated by Damian Lewis, and features Eric O'Neill as well as being mentioned in the seventh episode of The History Channel series America's Book of Secrets, as well as in the fifth episode of Netflix series Spycraft and was the subject of the 2021 documentary A Spy in the FBI. He was also the subject of the CBS News podcast detailing his life and espionage, Agent of Betrayal: The Double Life of Robert Hanssen.

Education

Hanssen graduated from Notre Dame University and later attended Northwestern University, where he earned an MBA. He was a highly educated individual, which contributed to his success within the FBI.

In summary, Robert Hanssen's life was marked by a complex interplay of loyalty, deception, and financial gain. His espionage activities significantly impacted U.S. national security, leading to severe consequences for his betrayal. Despite his financial earnings from espionage, Hanssen's life ended in imprisonment, a stark contrast to the life of a respected FBI agent he once led.

Hanssen met Bernadette "Bonnie" Wauck, a staunch Roman Catholic, while attending dental school at Northwestern. The couple married in 1968, and Hanssen converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism.

Hanssen was recalled yet again to Washington, D.C., in 1987. He was tasked with studying all known and rumored penetrations of the FBI to find the man who had betrayed Martynov and Motorin; this meant, in effect, that he was charged with searching for himself. Hanssen ensured that he did not reveal himself with his study, but in addition, he gave the entire study—including the list of all Soviets who had contacted the FBI about FBI moles—to the KGB in 1988. That same year, Hanssen, according to a government report, committed a "serious security breach" by revealing secret information to a Soviet defector during a debriefing. The agents working for him reported this breach to a supervisor, but no action was taken.

In 1994, Hanssen expressed interest in a transfer to the new National Counterintelligence Center, which coordinated counterintelligence activities. When told that he would have to take a lie detector test to join, Hanssen changed his mind. Three years later, convicted FBI mole Earl Edwin Pitts told the FBI that he suspected Hanssen due to the Mislock incident. Pitts was the second FBI agent to mention Hanssen by name as a possible mole, but superiors were still unconvinced, and no action was taken.