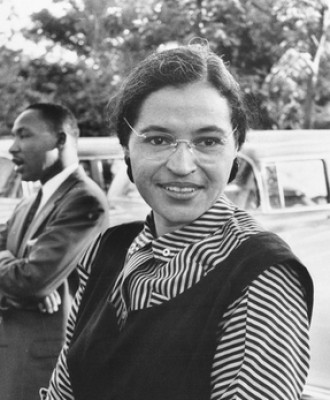

Age, Biography, and Wiki

Rosa Parks was born on February 4, 1913, and passed away on October 24, 2005. She is renowned for her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which began after she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in 1955. Her act sparked a citywide boycott, raising Martin Luther King Jr. to national prominence and leading to the U.S. Supreme Court's decision to outlaw segregation on city buses.

| Occupation | Activists |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 4 February 1913 |

| Age | 112 Years |

| Birth Place | Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S. |

| Horoscope | Aquarius |

| Country | U.S |

| Date of death | 24 October, 2005 |

| Died Place | Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

Height, Weight & Measurements

Unfortunately, specific details about Rosa Parks' height and weight are not widely documented in available sources.

In 1998, Parks filed a $5 billion lawsuit against American hip-hop duo Outkast and their record company claiming that the duo's song "Rosa Parks", released on their 1998 album Aquemini, used her name without permission, harming her reputation. After a federal court dismissed the lawsuit, Parks filed another suit in 2004 against BMG Rights Management, Arista Records, and LaFace Records. A settlement was reached in 2005, wherein Outkast and BMG agreed to pursue projects that would "enlighten today's youth about the significant role Rosa Parks played in making America a better place for all races" without admitting liability. The role of Steele, co-founder of the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute, and Parks's attorney, Gregory Reed, in these legal proceedings was subject to scrutiny, with some accusing them of "exploiting" Parks for their own again.

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Rosa Parks was married to Raymond Parks, a barber, from 1932 until his death in 1977. Their marriage was a long-standing one, providing mutual support throughout their lives.

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American activist in the civil rights movement. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. She is also sometimes known as the "mother of the civil rights movement".

Her mother, Leona (Edwards), was a teacher from Pine Level, Alabama. Her father, James McCauley, was a carpenter and mason from Abbeville, Alabama. Her name was a portmanteau of her maternal and paternal grandmothers' names: Rose and Louisa. In addition to her African ancestry, one of her great-grandfathers was of Scotch-Irish descent, and one of her great-grandmothers was of partial Native American ancestry.

To supplement the family's income, she worked on the plantation of Moses Hudson, who paid Black children 50 cents a day to pick cotton. Parks also learned quilting and sewing from her mother, completing her first quilt at the age of 10 and her first dress at 11. She attended the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, a century-old independent Black denomination founded by free Blacks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the early nineteenth century. Baptized at age two, she remained a member of the church throughout her life.

Parks initially attended school in a one-room schoolhouse at the local Mount Zion AME church. Because she suffered from chronic tonsilitis, she often missed school during the academic year, causing her mother to enroll her in summer school. When she was nine, she received a tonsillectomy from a doctor in Montgomery, Alabama, which improved her health. When she was eleven or twelve, she began attending the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, where she received vocational training. After the school closed in 1928, she transferred to Booker T. Washington Junior High School. She then attended a laboratory school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes, but dropped out to care for her ailing grandmother and mother.

In 1931, Rosa was introduced to her future husband, Raymond Parks, by a mutual friend. She was initially "[not] very interested in him" because of "some unhappy romantic experiences" and because of his light skin. However, Raymond eventually persuaded Rosa to ride with him in his car. At the time, automobile ownership was rare among Black men in Alabama. Rosa described Raymond as the "first real activist" she had met, admiring his opposition to racial prejudice. The two married on December 18, 1932, at Rosa's mother's house.

After her arrest, Parks was taken to Montgomery city hall, where she filled out her arrest forms. She was then taken to the city jail, where she was fingerprinted and photographed. After repeated requests, she was granted permission to call home, notifying her mother of her arrest and asking for Raymond to come. E. D. Nixon was also informed of Parks's arrest by his wife, who had heard about the arrest from a friend, who had learned about it from a bus passenger. Nixon drove down to the jail with Clifford and Virginia Durr and paid Parks's bail.

Upon arriving in Detroit, Rosa, Raymond, and Rosa's mother initially lived with Rosa's cousin before renting an apartment on Euclid Avenue. For a brief period beginning in October 1957, Parks moved to Hampton, Virginia to work at a Holly Tree Inn as a hostess. She returned to Detroit in December. She and her family continued to struggle financially. They lost their apartment in 1959 and moved into a meeting hall for the Progressive Civic League (PCL), a local Black professional organization. Rosa managed the treasury at the PCL's credit union while Raymond served as the meeting hall's caretaker.

Parks continued to experience health problems throughout the 1970s, and was injured several times after falling on ice. She also experienced personal losses, with Raymond dying of throat cancer in 1977 and her brother Sylvester dying of stomach cancer soon after. These personal struggles caused her to gradually withdraw from the civil rights movement. She learned of the death of Fannie Lou Hamer, once a close friend, from a newspaper, lamenting that Hamer was "dead quite before [she] knew of it", and that "no one mentioned it to [her]". Without support from her husband and unable to afford a nurse, Parks relocated her elderly mother, first to a retirement facility, then to a senior living apartment, where they lived together until her mother's death in 1979.

Parks continued to be politically active into the 1990s. In 1990, at a Washington, D.C. gala celebrating her birthday, Parks gave a speech calling for the release of anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela. She also attended the 1994 meeting of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America in Detroit alongside Jesse Jackson and Queen Mother Moore. In 1995, at the invitation of Louis Farrakhan, she participated in the Million Man March alongside Moore, Betty Shabazz, Dorothy Height, and Maya Angelou. During the 1990s, Parks authored several autobiographical works, including Rosa Parks: My Story in 1992, Quiet Strength in 1994, and Dear Mrs. Parks in 1997.

In Detroit, Parks's casket was displayed at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. A memorial service was held at the Greater Grace Temple on November 2. Attendees included Bill and Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. An honor guard accompanied Parks's casket via horse-drawn carriage to the service, where soul singer Aretha Franklin performed. After the service, a white hearse conveyed Parks's remains to Woodlawn Cemetery, where she was interred in a mausoleum alongside Raymond and her mother. The chapel was renamed the Rosa L. Parks Freedom Chapel in her honor

Scholars have also examined Parks's actions in relation to other, earlier instances of civil disobedience. Sociologist Barry Schwartz posits that while Parks became the celebrated symbol of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, many other individuals—including Browder, Colvin, Smith, and McDonald—played equally important and even more active roles in the struggle against segregation. Colvin herself felt a mix of emotions regarding Parks, glad that an adult had "stood up to the system" but also a feeling a sense of abandonment because the community had not supported her similar actions months prior. Browder's son maintained that Parks's prominence had overshadowed his mother's contributions, leaving her role largely unrecognized. Schwartz argues that accounts emphasizing the exceptional nature of Parks's refusal to move necessarily simplify the civil rights movement, creating a more accessible and symbolically compelling narrative.

| Parents | |

| Husband | Raymond Parks (m. 1932; died 1977) |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

Rosa Parks' net worth at the time of her passing was not substantial, as her work was primarily in civil rights activism rather than lucrative business ventures. Her income was largely derived from awards, honors, and occasional speaking engagements. Given her passing in 2005, her net worth would not apply in 2025, but her legacy continues to inspire and influence generations.

In 1933, Rosa completed her high school education with encouragement from Raymond. At the time in Alabama, only 7% of Black people held a high school diploma. Subsequently, she worked as a nurse's aide at St. Margaret's Hospital, sewing to supplement her income. In 1941, she began working at Maxwell Air Force Base, a training facility for air force cadets. The base was fully integrated, and Parks was able to take public transit alongside her white coworkers on-base. However, when she returned home, she was required to use segregated buses, which frustrated her. According to Parks, her time at Maxwell "opened her eyes up", providing an "alternative reality to the ugly racial policies of Jim Crow".

Black people constituted a majority of bus riders in Montgomery. According to the Women's Political Council, a Montgomery-based advocacy group, "three-fourths of the riders" on Montgomery buses were Black. Despite this, the first ten rows on each Montgomery bus were reserved for white passengers, while the last ten rows were designated for Black passengers. Segregation in the middle rows was enforced at the driver's discretion. While city ordinances did not require patrons to give up their seats, bus drivers frequently demanded Black passengers do so to accommodate white riders. Furthermore, Black passengers were sometimes required to pay their fares at the front of the bus, then exit and re-board through the back door.

According to United States Representative Edward Vaughn, after reports of Skipper's conduct circulated, vigilantes proceeded to search for and assault him. Skipper was arrested on August 31. While many commentators saw Parks's assault as evidence of the moral decline of Black youth, Parks cautioned against "read[ing] too much into the attack" and expressed compassion for Skipper, acknowledging "the conditions that made him". After the assault, Parks moved from downtown Detroit to a gated community. Learning of Parks's move, Little Caesars owner Mike Ilitch offered to pay for her housing expenses indefinitely. According to journalist Christopher Botta, writing for the Sports Business Journal, funds from Ilitch were regularly deposited into a trust managed on Parks's behalf.

Representative Conyers introduced Concurrent Resolution 61, which received Senate approval on October 29, 2005, allowing Parks's remains to lie in state at the United States Capitol rotunda from October 30 to October 31. Her remains were transported to the rotunda by the United States National Guard. 40,000 mourners came to pay their respects, with President George W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush laying a wreath on her coffin. Parks was the 31st individual, and the second private citizen, to be laid in state. A public memorial was also held at the Metropolitan AME Church before her remains were returned to Detroit.

Career, Business, and Investments

Rosa Parks' career was centered around civil rights activism. She was a key figure in the NAACP, serving as the youth leader and secretary for the Montgomery chapter from 1943 to 1957. Her involvement in the Montgomery Bus Boycott marked a significant turning point in the civil rights movement. She continued to advocate for civil rights throughout her life, receiving numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Parks began attending meetings of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1943 after seeing a picture of a former classmate of hers, Johnnie Carr, at a meeting. In December 1943, she was elected secretary of the chapter. Parks later explained that she accepted the role (which was considered a woman's position at the time) because "[she] was the only woman there, and they needed a secretary, and [she] was too timid to say no". She and Raymond were also members of the Voter's League, a local organization focused on increasing Black voter registration. There were numerous obstacles preventing Black people from registering to vote in Alabama during this period, including poll taxes, literacy tests, intrusive questions on voter registration applications, and retaliation by employers. As of 1940, less than 0.1% of Black Montgomerians were registered to vote. Encouraged by NAACP activist E. D. Nixon, Parks attempted to register three times beginning in 1943, finally succeeding in 1945.

After Parks's arrest, Nixon conferred with Clifford about the possibility of adopting Parks's arrest as a test case. The two favored Parks because of her high standing in the Black community, her respectable manners, and her "firm quiet spirit", which, according to Durr, "would be needed for the long battle ahead". After being approached by Nixon to be a test case, Parks consulted with her family. Despite concerns about potential violent retaliation, she ultimately consented. Attorney Fred Gray agreed to represent Parks in court, and WPC President Jo Ann Robinson was notified of the case. The WPC began planning for a one-day boycott of Montgomery buses on December 5, 1955, the day of Parks's trial. Under the guise of grading exams, Robinson collaborated with two students at Alabama State College to produce 35,000 leaflets announcing the boycott using a mimeograph provided by the college's business chair, John Cannon.

At a December 6 press conference, King declared that the boycott would continue until all demands had been satisfied. However, at a meeting on December 8, city and bus company officials dismissed MIA's demands. The MIA began developing a parallel transportation network for Black Montgomerians to support the boycott. Parks served temporarily as a dispatcher, coordinating transportation within the MIA's ride-sharing system. She was ostracized by her coworkers at Montgomery Fair, where she worked as a seamstress. In January 1956, she was terminated. A week later, Raymond was also terminated from his job at Maxwell Air Force Base. That same month, Montgomery Police Commissioner Clyde Sellers initiated a "Get Tough" policy, harassing Black pedestrians and boycott participants. Boycott organizers, including Parks, received regular death threats. In February, a state grand jury declared the boycott illegal, leading to the arrest of 115 boycott leaders, including Parks. However, ultimately only King was tried. The boycott continued.

In 1957, after the end of the boycott, Virginia Durr offered her a position at Highlander in hopes of organizing a Black voter registration campaign in Montgomery. Parks declined, citing the school's location in Tennessee and concerns about potential reprisals if she were to speak in Alabama, Mississippi, or Louisiana. She also disagreed with King and the emerging Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) regarding their impending airport desegregation campaign. Tensions between King and Nixon caused a rift in the MIA, with Parks taking Nixon's side. However, tensions developed between Nixon and Parks as well, and her health further deteriorated. In August 1957, prompted by economic insecurity, threats to her safety, and divisions within the MIA leadership, she left Montgomery for Detroit, where her brother, Sylvester, and her cousins, Thomas Williamson and Annie Cruse, lived. The MIA, embarrassed by her decision to move, raised $500 for her as a "going-away present".

In early 1960, Parks's health further deteriorated, necessitating multiple surgeries. She and her family incurred significant debt due to unpaid medical bills. She received donations from the MIA and PCL, and the Black press began to write about her financial difficulties. In 1961, after her health improved and she found employment at Stockton Sewing Company, the family moved to Detroit's Virginia Park neighborhood. Raymond also secured employment at a local barber shop.

Parks was robbed and assailed in her home on August 30, 1994, at age 81. The assailant, Joseph Skipper, broke down her back door, falsely claiming to have deterred an intruder and demanding a reward of $3. After Parks complied, he demanded additional money and assaulted her, punching her in the face. Eventually, Parks agreed to give Skipper all of the money she had: $103. Parks then called Steele, co-founder of the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute, who called the police.

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Parks joined actor Danny Glover and activists Harry Belafonte and Gloria Steinem in signing an open letter that cautioned against a "military response" and advocated for international collaboration. Later, in 2002, Parks received an eviction notice from her $1,800 per month apartment for non-payment of rent. Parks was incapable of managing her own financial affairs by this time due to age-related physical and mental decline. Her rent was paid from a collection taken by Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in Detroit. When her rent became delinquent and her impending eviction was publicized in 2004, executives of the ownership company announced they had forgiven the back rent and would allow Parks, by then 91 and in extremely poor health, to live rent-free in the building for the remainder of her life. Steele, co-founder of the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute, defended Parks's care and stated that the eviction notices were sent in error. Several of Parks's family members alleged that her financial affairs had been mismanaged.

Parks received numerous awards as a result of her contributions to the civil rights movement. The SCLC established the Rosa Parks Freedom Award in 1963, though Parks herself did not receive it until 1972. In 1965, she received the "Dignity Overdue" award from the Afro-American Broadcasting Company and was honored at a ceremony held at the Ford Auditorium in Detroit. The Capitol Press Club presented her with the Martin Luther King Jr. Award in 1968. In 1979, the NAACP awarded her the Spingarn Medal, citing her "quiet courage and determination" in refusing to relinquish her seat. The NAACP further recognized her with their own Martin Luther King Jr. Award in 1980. In 1983, she was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame. She also received the Candace Award in 1984 from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women.

Many locations and institutions have been named in honor of Parks. At the behest of her friend Louise Tappes, Detroit's 12th street was renamed "Rosa Parks Boulevard". A bronze sculpture of Parks was displayed at the National Portrait Gallery in 1991. Michigan designated February 4 as Rosa Parks Day in 1997. In 2000, at the cost of $10 million, Troy University opened the Rosa Parks Library and Museum at the site of Parks's arrest. Parks's apartment in Montgomery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. The bus on which Parks refused to move was restored with funding from the Save America's Treasures program and placed on display at The Henry Ford museum in 2003.

On January 4, 2016, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reviewed a lawsuit brought by the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development against American retail corporation Target. In the lawsuit, the institute alleged that Target infringed on Parks's rights to her name and likeness by selling merchandise using her name, contrary to a Michigan law safeguarding against the unauthorized use of a person's identity for commercial gain. The court's ruling, given by Judge Robin S. Rosenbaum, stated that "the use of Rosa Parks's name and likeness in the books, movie, and plaque are necessary to chronicling and discussing the history of the Civil Rights Movement — matters quintessentially embraced and protected by Michigan's qualified privilege", permitting the sale of the items at Target.

Social Network

Rosa Parks did not have a personal social media presence, as these platforms were not prevalent during her lifetime. However, her legacy is widely celebrated and shared across various social media platforms today.

Montgomery passed a city ordinance segregating bus passengers by race in 1900, before statewide segregation was implemented. Montgomery's Black residents conducted boycotts against segregated streetcars between 1900 and 1902, coinciding with similar boycotts and protests in other southern cities. The boycotts resulted in an amendment to the city ordinance, which stipulated that "no rider had to surrender a seat unless another was available". However, many drivers failed to follow the ordinance. Altercations between bus drivers and Black passengers were frequent. According to historian Cheryl Phibbs, "bus drivers were given policeman-like authority to determine where racial divisions were enforced". They were also generally armed.

Parks played a critical role in John Conyers's 1964 congressional campaign. She persuaded King, who was generally reluctant to endorse local candidates, to appear with Conyers, boosting the novice candidate's profile. When Conyers was elected, he hired her as a secretary and receptionist for his congressional office in Detroit. As part of her position, Parks engaged with Conyers's constituents, focusing on addressing socio-economic challenges such as welfare, education, job discrimination, and affordable housing. Through regular visits to schools, hospitals, senior citizen facilities, and community gatherings, she ensured Conyers remained connected to grassroots concerns. Conyers later recalled of Parks that "you treated her with deference because she was so quiet, so serene—just a very special person".

In 1999, Parks filmed a cameo appearance for the television series Touched by an Angel. She was played by Iris Little-Thomas in the 2001 film Boycott, directed by Clark Johnson, and by Angela Bassett in the 2002 biopic The Rosa Parks Story, directed by Julie Dash. She was also the subject of the short documentary film Mighty Times: The Legacy of Rosa Parks, which was nominated for Best Documentary Short Film at the 75th Academy Awards.

The 2002 film Barbershop, directed by Tim Story, garnered controversy due to its inclusion of a scene discussing Parks's actions. In the scene, Eddie, played by Cedric the Entertainer, downplays Rosa Parks's role in the civil rights movement, arguing that her actions were simply those of a tired person and that many others had performed similar acts of defiance without receiving recognition. He attributes her fame to her NAACP connections and association with King. Jesse Jackson and activist Al Sharpton criticized the movie, with Sharpton calling for a boycott of the film. However, NAACP President Kweisi Mfume stated he thought the controversy was "overblown". Parks herself boycotted the 2003 NAACP Image Awards ceremony, which Cedric hosted.

Education

Rosa Parks' formal education was limited due to racial segregation and economic constraints. She attended the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, a private school for African-American girls, and later enrolled in the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes but did not complete her studies due to financial difficulties.

In summary, Rosa Parks' life was marked by her unwavering dedication to civil rights rather than financial wealth. Her legacy remains invaluable, inspiring generations to fight for equality and justice.

Prior to Parks's refusal to move, numerous Black Montgomerians had engaged in similar acts of resistance against segregated public transportation. After Parks's arrest in 1955, local activists decided to use her case as a test case against segregation, leading the Women's Political Council (WPC) to organize a one-day bus boycott on the day of her trial. The boycott was widespread, with many Black Montgomerians refusing to ride the buses that day. After Parks was found guilty of violating state law, it was extended indefinitely, with the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) organizing its own community transportation network to sustain it. During this time, Parks and other boycott leaders faced harassment, ostracization, and various legal obstacles. The boycott lasted for 381 days, finally concluding after segregation on Montgomery buses was deemed unconstitutional in the court case Browder v. Gayle.

After dropping out of school, Parks worked on her family's farm and as a domestic worker in white households. Black women in Alabama who worked as domestic workers often experienced sexual violence, as exemplified by the rape of Murdus Dixon, a 12-year-old girl who was threatened at knifepoint and raped in Birmingham, Alabama. During the 1950s or 60s, Parks wrote an account of an incident where a white man named "Mr. Charlie" attempted to sexually assault her. In her account, she verbally resists Mr. Charlie's advances and denounces his racism. The account concludes with her attempting to read a newspaper while ignoring him. While the account may have been partially or entirely fictionalized, biographer Jeanne Theoharis notes that many of the elements of the account "correspond to Parks's life", speculating that Parks "wrote [the account] as an allegory to suggest larger themes of domination and resistance", or that, "given that more than twenty-five years had passed before she wrote [the account] down, she augmented what she said to Charlie that evening with all the points that she had wished to make as she resisted his advances".

Beginning in 1954, Parks began working as a seamstress for Clifford and Virginia Durr, a white couple. Politically liberal and opposed to segregation, the Durrs became her friends. They encouraged, and eventually helped sponsor, Parks to attend the Highlander Folk School, an activist training center in Monteagle, Tennessee, in the summer of 1955. There, Parks was mentored by the veteran organizer Septima Clark. Parks later reflected that her experience at Highlander provided her with a vision of a unified, integrated society, marking the first time in her adult life that she witnessed "people of all races and backgrounds" interacting harmoniously. Later, in August 1955, she attended a Montgomery meeting concerning the lynching of Emmett Till. According to Theoharis, Parks was "heartened by the attention that people managed to get to the [Till] case", since the custom was to "keep things covered up".

Before December 1955, several people were arrested for declining to give up their seats on Montgomery buses. Maxwell Air Force Base employee Viola White was arrested in 1944, and Mary Wingfield was arrested in 1949. Teenager Mary Louise Smith was arrested in October 1954. In March 1955, Claudette Colvin, a fifteen-year-old student at Booker T. Washington Magnet High School, was also arrested. Additional arrests included Aurelia Browder on April 29, 1955, and Susie McDonald on October 21, 1955. Smith, Colvin, Browder, and McDonald were the plaintiffs in the 1956 lawsuit Browder v. Gayle. Black activists, including members of the WPC and NAACP, considered Smith and Colvin as test cases for a community bus boycott, but ultimately determined that they were not suitable candidates.

During the 1979/1980 academic year, Parks visited the Black Panther school in Oakland, California. As part of her visit, she attended a student play dramatizing her refusal to move in 1955, staying after to answer the students' questions. According to the school's director, Ericka Huggins, Parks "loved" the visit, praising the school's instructors and the Black Panther Party for their work. Huggins later said of Parks's visit: "I consider Rosa Parks a radical woman, a revolutionary woman, showing up in real time at an elementary school run by the Black Panther Party."

During the 1980s, Parks continued to take part in various social and political causes. In 1981, she wrote to attorney Chokwe Lumumba in support of arrested activists from the Black Liberation Army, the May 19th Communist Organization, the RNA, and Weather Underground. She also participated in the Free South Africa Movement, which opposed apartheid in South Africa. Working with the movement, Parks participated in anti-apartheid demonstrations in Washington, D.C. and Berkeley, California, and in the National Conference Against Apartheid, which took place at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. She supported Jesse Jackson's 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns. Speaking on his behalf at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, Parks said: "At some point we should step aside and let the younger ones take over. But we first must take care of our young people to make sure that they have the rights of first-class citizens... And when we see so little done by so many, we just will not give up."

In 1987, Parks co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development with Elaine Eason Steele. The purpose of the institute, which was influenced by Parks's experiences at Montgomery Industrial School for Girls and Highlander, is to develop youth leaders' capabilities in advancing civil rights initiatives. The institute also offers "Pathways to Freedom" bus tours, which introduce young people to important civil rights and Underground Railroad sites throughout the country. Parks also served on the Board of Advocates for Planned Parenthood. Unrelated to her activism, she donated several quilts made by members of her family to the Detroit Historical Museum.

On February 1, Obama proclaimed February 4, 2013, as the "100th Anniversary of the Birth of Rosa Parks", calling "upon all Americans to observe this day with appropriate service, community, and education programs to honor Rosa Parks's enduring legacy". The Henry Ford museum designated February 4, 2013, as a "National Day of Courage". Also on February 4, the United States Postal Service unveiled a postage stamp in Parks's honor.

In 2014, a statue of Parks was dedicated at the Essex Government Complex in Newark, New Jersey. Rosa Parks station opened in Paris, France in 2015. In 2016, Parks's former residence in Detroit was threatened with demolition. A Berlin-based American artist, Ryan Mendoza, arranged to have the house disassembled, moved to his garden in Germany, and partly restored and converted into a museum honoring Parks. In 2018, the house was moved back to the United States. While Brown University was initially planning to exhibit the house, the display was cancelled. The house was eventually exhibited at the WaterFire Arts Center in Providence, Rhode Island. Also in 2018, Continuing the Conversation, a public sculpture of Parks, was unveiled on the main campus of Georgia Tech. Another statue of Parks was unveiled in Montgomery in 2019. In 2021, a bust of Rosa Parks was added to the Oval Office when Joe Biden began his presidency. A statue of Parks was approved for the Alabama State Capitol grounds in 2023.

Many popular narratives surrounding Parks portray her as a heroine, with Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist claiming that Parks's refusal to move was "not an intentional attempt to change a nation, but a singular act aimed at restoring the dignity of the individual". Writing in the Florida State University Law Review, civil rights advocate A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. describes Parks as a "heroine" who exemplified both "raw courage" and "genteelness". Academic Kenan İli characterizes Parks as an "icon of leadership", emphasizing her "quiet strength" and "feminine dignity". He argues that Parks's actions, driven by "values and integrity", served as a powerful catalyst for change, inspiring both a city and a nation to confront their systemic injustices.

Theoharis, in her 2015 biography The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, argues that the popular narrative of Rosa Parks as a "quiet" and "accidental" figure in the civil rights movement obscures her lifelong radical activism and political philosophy, as well as the "variety of struggles" that she took part in. She describes the "quiet" portrayal of Parks as a "gendered caricature", contending that interviewers misinterpreted her words in an attempt to form their own narratives around Parks. Academic Riché Richardson similarly critiques the "uses, abuses, and appropriations" of Parks's legacy in contemporary political discourse, particularly the ways in which her image has been manipulated to serve various political agendas.

Academic Dennis Carlson argues that the popular conception of Rosa Parks transforms her into a "monumentalist hero", a figure used to reinforce conservative narratives of American history and morality. According to Carlson, this portrayal isolates her act of defiance, framing it as an individual, legally-focused moment of courage that both ignited and calmed a potentially violent Black community. Biographer Darryl Mace speculates that Parks's passive and quiet public image was shaped both by the gendered norms of the 1950s and the male-dominated leadership of the civil rights movement. He contends that Parks was relegated to gendered roles in the movement, and that her refusal to move was framed within a narrative of female vulnerability.