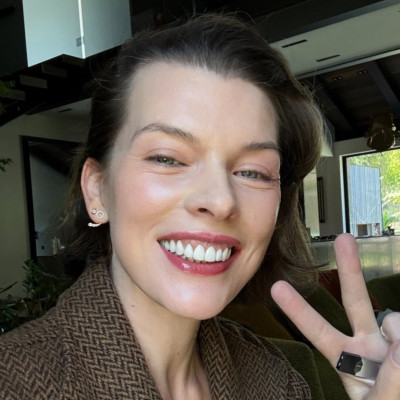

Age, Biography, and Wiki

Greta Garbo was born on September 18, 1905, in Stockholm, Sweden. She passed away on April 15, 1990, at the age of 84. Garbo's early life was marked by poverty, but she found solace in her acting talents. She rose to fame in the 1920s and 1930s, becoming one of the most iconic actresses of her time. Her career was marked by her portrayal of tragic characters and understated yet powerful performances. Garbo's biography is a testament to her remarkable journey from humble beginnings to international stardom.

| Occupation | Actress |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 18 September 1905 |

| Age | 120 Years |

| Birth Place | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Horoscope | Virgo |

| Country | Sweden |

| Date of death | 15 April, 1990 |

| Died Place | New York City, U.S. |

Height, Weight & Measurements

Greta Garbo was known for her statuesque figure, standing at approximately 5 feet 7 inches (170 cm) tall. Her weight and measurements were not widely documented, but her physical presence on screen was unmistakable.

| Height | 5 feet 7 inches |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Garbo never married and had no children. She maintained a private personal life, focusing on her career and later on her investments. Her decision to live a frugal life allowed her to accumulate wealth through smart financial decisions.

Her parents met in Stockholm, where her father had been visiting from Frinnaryd. He moved to Stockholm to become independent and worked as a street cleaner, grocer, factory worker and butcher's assistant. He married Anna, who moved from Högsby. The family was impoverished and lived in a three-bedroom cold-water flat at Blekingegatan No. 32. They raised their three children in a working-class district regarded as the city's slum. Garbo later recalled:

"It was eternally grey—those long winter's nights. My father would be sitting in a corner, scribbling figures on a newspaper. On the other side of the room, my mother is repairing ragged old clothes, sighing. We children would be talking in very low voices, or just sitting silently. We were filled with anxiety, as if there were danger in the air. Such evenings are unforgettable for a sensitive girl, but also for a girl like me. Where we lived, all the houses and apartments looked alike, their ugliness matched by everything surrounding us." Garbo was a shy daydreamer as a child. She disliked school and preferred to play alone. She was a natural leader who became interested in theatre at an early age. She directed her friends in make-believe games and performances, and dreamed of becoming an actress. Later, she would participate in amateur theatre with her friends and frequent the Mosebacke Theatre. At the age of 13, Garbo graduated from school, and, typical of a Swedish working-class girl at that time, she did not attend high school. She later acknowledged a resulting inferiority complex. The Spanish flu spread throughout Stockholm in the winter of 1919 and her father, to whom she was very close, became ill and lost his job. Garbo cared for him, taking him to the hospital for weekly treatments. He died in 1920 when she was 14 years old.

In 1925, Garbo, who was unable to speak English, was brought to Hollywood from Sweden at the request of Mayer. After a 10-day crossing on the SS Drottningholm in July, Garbo and Stiller arrived in New York where they remained for more than six months without word from MGM. They decided to travel to Los Angeles on their own but another five weeks passed without contact from the studio. On the verge of returning to Sweden, Garbo wrote her boyfriend back home, "You're quite right when you think I don't feel at home here ... Oh, you lovely little Sweden, I promise that when I return to you, my sad face will smile as never before." A Swedish friend in Los Angeles helped by contacting MGM production boss Irving Thalberg, who agreed to give Garbo a screen test. According to author Frederick Sands, "the result of the test was electrifying. Thalberg was impressed and began grooming the young actress the following day, arranging to fix her teeth, making sure she lost weight and giving her English lessons."

During her rise to stardom, film historian Mark Vieira notes, "Thalberg decreed that henceforth, Garbo would play a young, but worldly wise, woman." However, according to Thalberg's actress wife, Norma Shearer, Garbo did not necessarily agree with his ideas stating "Miss Garbo at first didn't like playing the exotic, the sophisticated, the woman of the world. She used to complain, "Mr. Thalberg, I am just a young gur-rl!" Irving tossed it off with a laugh. With those elegant pictures, he was creating the Garbo image". Although she expected to work with Stiller on her first film, she was cast in Torrent (1926), an adaptation of a novel by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, with director Monta Bell. She replaced Aileen Pringle, 10 years her senior, and played a peasant girl turned singer, opposite Ricardo Cortez. Torrent was a hit, and, despite its cool reception by the trade press, Garbo's performance was well received.

Garbo selected George Cukor's romantic drama Camille (1936) as her next project. Thalberg cast her opposite Robert Taylor and former co-star, Lionel Barrymore. Cukor carefully crafted Garbo's portrayal of Marguerite Gautier, a lower-class woman, who becomes the world-renowned mistress Camille. Production was marred, however, by the sudden death of Thalberg, then only thirty-seven, which plunged the Hollywood studios into a "state of profound shock", writes David Bret. Garbo had grown close to Thalberg and his wife, Norma Shearer, and had often dropped by their house unannounced. Her grief for Thalberg, some believe, was more profound than for John Gilbert, who died earlier that same year. His death also added to the sombre mood required for the closing scenes of Camille. When the film premiered in New York on 12 December 1936, it became an international success, Garbo's first major success in three years. She won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress for her performance, and she was nominated once more for an Academy Award. Garbo regarded Camille as her favorite out of all of her films.

In 1937, Garbo met Leopold Stokowski, then conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, with whom she had a brief, but highly publicized relationship while the pair traveled throughout Europe the following year; whether the relationship was romantic or platonic is uncertain. In his diary, Erich Maria Remarque discusses a liaison with Garbo in 1941, and in his memoir, Cecil Beaton described an affair with her in 1947 and 1948. In 1941, she met the Russian-born millionaire George Schlee, who was introduced to her by his wife, fashion designer Valentina. Nicholas Turner, Garbo's close friend for 33 years, said that, after she bought an apartment in the same building, "Garbo moved in and took Schlee from Valentina right away." Schlee would divide his time between the two, becoming Garbo's close companion and advisor until his death in 1964.

Garbo was portrayed by Betty Comden in the film Garbo Talks (1984). The plot concerns a dying Garbo fan (Anne Bancroft) whose last wish is to meet her idol. Her son (played by Ron Silver) diligently searches for the elusive Garbo, determined to fulfill his mother's wish.

Garbo was nominated four times for the Academy Award for Best Actress. In 1930, a performer could receive a single nomination for their work in more than one film. Garbo received her nomination for her work in both Anna Christie and for Romance. She lost out to Irving Thalberg's wife, Norma Shearer, who won for The Divorcee. In 1937, Garbo was nominated for Camille, but Luise Rainer won for The Good Earth. Finally, in 1939, Garbo was nominated for Ninotchka, but again came away empty-handed. Gone With the Wind swept the major awards, including Best Actress, which went to Vivien Leigh. In 1954, however, she was awarded an Academy Honorary Award "for her luminous and unforgettable screen performances". Predictably, Garbo did not show up at the ceremony, and the statuette was mailed to her home address.

| Parents | |

| Husband | |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

At the time of her death in 1990, Greta Garbo's net worth was approximately $32 million. Adjusted for inflation, her net worth would be equivalent to about $70 million today, although some estimates suggest it could be as high as $90 million. Her earnings from films were substantial, with reports indicating she earned over $3 million for her movies, which is equivalent to over $40 million today.

After nearly a year of negotiations, Garbo agreed to renew her contract with MGM on the condition that she would star in Queen Christina (1933), and her salary would be increased to $300,000 per film. The film's screenplay had been written by Salka Viertel; although reluctant to make the movie, MGM relented at Garbo's insistence. For her leading man, MGM suggested Charles Boyer or Laurence Olivier, but Garbo rejected both, preferring her former co-star and lover John Gilbert. The studio balked at the idea of casting Gilbert, fearing his declining career would hurt the film's box-office, but Garbo prevailed. Queen Christina was a lavish production, becoming one of the studio's biggest productions at the time. Publicized as "Garbo returns", the film premiered in December 1933 to positive reviews and box-office triumph and became the highest-grossing film of the year. The movie, however, met with controversy upon its release; censors objected to the scenes in which Garbo disguised herself as a man and kissed a female co-star.

Although her domestic popularity was undiminished in the early 1930s, high profits for Garbo's films after Queen Christina depended on the foreign market for their success. The type of historical and melodramatic films she began to make on the advice of Viertel were highly successful abroad, but considerably less so in the United States. In the midst of the Great Depression, American screen audiences seemed to favor "home-grown" screen couples, such as Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. David O. Selznick wanted to cast Garbo as the dying heiress in Dark Victory (eventually released in 1939 with other leads), but she chose Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (1935), in which she played another of her renowned roles. Her performance won her the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress. The film was successful in international markets, and had better domestic rentals than MGM anticipated. Still, its profit was significantly diminished because of Garbo's exorbitant salary.

The Cole Porter song "You're the Top" makes a passing reference to the importance of her salary. Garbo is mentioned in The Kinks' 1972 song "Celluloid Heroes" and the 1977 song "Right Before Your Eyes" by Ian Thomas, which was covered by America in 1982. Greta Garbo is mentioned in the 1981 Kim Carnes hit song "Bette Davis Eyes" and she was the subject of the 1985 Freddie Mercury song, "Living On My Own". The 1988 song, "Garbo" by Austrian musician Falco serves as a tribute in the form of a love song. In the 1990 song "Vogue" by Madonna, Greta Garbo is the first mentioned of a list of stars from Hollywood's Golden Age.

Career, Business, and Investments

Garbo's career in Hollywood spanned over two decades, with her last film being "Two-Faced Woman" in 1941. She retired at the age of 35 and spent the next several decades collecting art and investing in stocks and bonds. Her art collection and stock portfolio were valued at tens of millions of dollars at the time of her death. Her business acumen allowed her to amass a significant fortune, which she left to her niece upon her passing.

Garbo launched her career with a secondary role in the 1924 Swedish film The Saga of Gösta Berling. Her performance caught the attention of Louis B. Mayer, chief executive of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), who brought her to Hollywood in 1925. She stirred interest with her first American silent film, Torrent (1926). Garbo's performance in Flesh and the Devil (1926), her third movie in the United States, made her an international star. In 1928, Garbo starred in A Woman of Affairs, which catapulted her to MGM's highest box-office star, surpassing the long-reigning Lillian Gish. Other well-known Garbo films from the silent era are The Mysterious Lady (1928), The Single Standard (1929), and The Kiss (1929).

Many critics and film historians consider her performance as the doomed courtesan Marguerite Gautier in Camille (1936) to be her finest and the role gained her a third Academy Award nomination. However, Garbo's career soon declined and she became one of many stars labelled box office poison in 1938. Her career revived with a turn to comedy in Ninotchka (1939), which earned her a fourth Academy Award nomination. Two-Faced Woman (1941), a box-office flop, was the last of her 28 films. Following this commercial failure, she continued to be offered movie roles, though she declined most of them. Those she did accept failed to materialize, either due to lack of funds or because she dropped out during filming. In 1954, Garbo was awarded an Academy Honorary Award "for her luminous and unforgettable screen performances".

Garbo first worked as a soap-lather girl in a barber shop before taking a job in the PUB department store where she ran errands and worked in the millinery department. After modeling hats for the store's catalogues, Garbo earned a more lucrative job as a fashion model at Nordiska Kompaniet. In 1920, a director of film commercials for the store cast Garbo in roles advertising women's clothing. Her first commercial premiered on 12 December 1920 In 1922, Garbo caught the attention of director Erik A. Petschler, who gave her a part in his short comedy, Peter the Tramp (Luffar-Petter ).

From 1922 to 1924, she studied at the Royal Dramatic Training Academy in Stockholm. She was recruited in 1924 by the Finnish director Mauritz Stiller to play a principal part in his film The Saga of Gösta Berling, a dramatization of the famous novel by Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf, which also featured the actor Lars Hanson. Stiller became her mentor, training her as a film actress and managing all aspects of her nascent career. She followed her role in Gösta Berling with a starring role in the German film Die freudlose Gasse (Joyless Street or The Street of Sorrow, 1925), directed by G. W. Pabst and co-starring Asta Nielsen. She praised Asta and said: "In terms of expression and versatility, I am nothing to her."

Accounts differ on the circumstances of her first contract with Louis B. Mayer, at that time vice president and general manager of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Victor Seastrom, a respected Swedish director at MGM, was a friend of Stiller and encouraged Mayer to meet him on a trip to Berlin. There are two recent versions of what happened next. In one, Mayer, always looking for new talent, had done his research and was interested in Stiller. He made an offer, but Stiller demanded that Garbo be part of any contract, convinced that she would be an asset to his career. Mayer balked, but eventually agreed to a private viewing of Gösta Berling. He was immediately struck by Garbo's magnetism and became more interested in her than in Stiller. "It was her eyes," his daughter recalled him saying, "I can make a star out of her." In the second version, Mayer had already seen Gösta Berling before his Berlin trip, and Garbo, not Stiller, was his primary interest. On the way to the screening, Mayer said to his daughter: "This director is wonderful, but what we really ought to look at is the girl ... The girl, look at the girl!" After the screening, his daughter reported, he was unwavering: "I'll take her without him. I'll take her with him. Number one is the girl."

After her lightning ascent, Garbo made eight more silent films, and all were hits. She starred in three of them with the leading man John Gilbert. About their first movie, Flesh and the Devil (1926), silent film expert Kevin Brownlow states that "she gave a more erotic performance than Hollywood had ever seen." Their on-screen chemistry soon translated into an off-camera romance, and by the end of the production, they began living together. The film also marked a turning point in Garbo's career. Vieira wrote: "Audiences were mesmerized by her beauty and titillated by her love scenes with Gilbert. She was a sensation." Profits from her third movie with Gilbert, A Woman of Affairs (1928), catapulted her to top Metro star of the 1928–1929 box office season, usurping the long-reigned silent queen Lillian Gish. In 1929, reviewer Pierre de Rohan wrote in the New York Telegraph: "She has glamour and fascination for both sexes which have never been equaled on the screen."

After the box-office failure of Conquest, MGM decided a change of pace was needed to resurrect Garbo's career. For her next movie, the studio teamed her with producer-director Ernst Lubitsch to film Ninotchka (1939), her first comedy. The film was one of the first Hollywood movies which, under the cover of a satirical, light romance, depicted the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin as being rigid and gray when compared to Paris in its pre-war years. Ninotchka premiered in October 1939, publicized with the catchphrase "Garbo laughs!", commenting on the departure of Garbo's serious and melancholy image as she transferred to comedy. Favoured by critics and box-office success in the United States and abroad, it was banned in the Soviet Union.

Although Garbo felt humiliated by the negative reviews of Two-Faced Woman, she did not intend to retire at first. But her films depended on the European market, and when it fell through because of the war, finding a vehicle was problematic for MGM. Garbo signed a one-picture deal in 1942 to make The Girl from Leningrad, but the project quickly dissolved. She still thought she would continue when the war was over, though she was ambivalent and indecisive about returning to the screen. Salka Viertel, Garbo's close friend and collaborator, said in 1945: "Greta is impatient to work. But on the other side, she's afraid of it." Garbo also worried about her age. "Time leaves traces on our small faces and bodies. It's not the same anymore, being able to pull it off." George Cukor, director of Two-Faced Woman, and often blamed for its failure, said: "People often glibly say that the failure of Two-Faced Woman finished Garbo's career. That's a grotesque over-simplification. It certainly threw her, but I think that what really happened was that she just gave up. She didn't want to go on."

Social Network

Garbo lived a reclusive life away from the public eye after her retirement. She did not engage in social media as it did not exist during her lifetime. Her legacy, however, continues to inspire and influence new generations of actors and fans.

Over time, Garbo would decline all opportunities to return to the screen. In her retirement, she shunned publicity, led a private life, and became an art collector whose paintings included works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pierre Bonnard and Kees van Dongen. Although she refused throughout her life to talk to friends about her reasons for retiring, four years before her death, she told Swedish biographer Sven Broman: "I was tired of Hollywood. I did not like my work. There were many days when I had to force myself to go to the studio ... I really wanted to live another life."

Garbo's success in her first American film led Thalberg to cast her in a similar role in The Temptress (1926), based on another Ibáñez novel. In this, her second film, she played opposite the popular star Antonio Moreno but was given top billing. Her mentor Stiller, who had persuaded her to take the part, was assigned to direct. For both Garbo (who did not want to play another vamp and did not like the script any more than she did the first one) and Stiller, The Temptress was a harrowing experience. Stiller, who spoke little English, had difficulty adapting to the studio system and did not get on with Moreno, was fired by Thalberg and replaced by Fred Niblo. Re-shooting The Temptress was expensive, and even though it became one of the top-grossing films of the 1926–1927 season, it was the only Garbo film of the period to lose money. However, Garbo received rave reviews, and MGM had a new star.

In late 1929, MGM cast Garbo in Anna Christie (1930), a film adaptation of the 1922 play by Eugene O'Neill, her first speaking role. The screenplay was adapted by Frances Marion, and the film was produced by Irving Thalberg and Paul Bern. Sixteen minutes into the film, she famously utters her first line, "Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side, and don't be stingy, baby." The film premiered in New York City on 21 February 1930, publicized with the catchphrase "Garbo talks!", and was the highest-grossing film of the year. Her performance received positive reviews; Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times remarked that Garbo was "even more interesting through being heard than she was in her mute portrayals. She reveals no nervousness before the microphone and her careful interpretation of Anna can scarcely be disputed." Garbo received her first Academy Award for Best Actress nomination for her performance, although she lost to MGM colleague Norma Shearer. Her nomination that year included her performance in Romance (1930). After filming ended, Garbo—along with a different director and cast—filmed a German-language version of Anna Christie that was released in December 1930. The film's success certified Garbo's successful transition to talkies. In her follow-up film, Romance, she portrayed an Italian opera star, opposite Lewis Stone. She was paired opposite Robert Montgomery in Inspiration (1931), and her profile was used to boost the career of the relatively unknown Clark Gable in Susan Lenox (Her Fall and Rise) (1931). Although the films did not match Garbo's success with her sound debut, she was ranked as the most popular female star in the United States in 1930 and 1931.

She was offered many roles both in the 1940s and throughout her retirement years but rejected all but a few of them. In the few instances when she did accept them, the slightest problem led her to drop out. Although she refused throughout her life to talk to friends about her reasons for retiring, four years before her death, she told Swedish biographer Sven Broman: "I was tired of Hollywood. I did not like my work. There were many days when I had to force myself to go to the studio ... I really wanted to live another life."

From the early days of her career, Garbo avoided industry social functions, preferring to spend her time alone or with friends. She never signed autographs or answered fan mail, and rarely gave interviews. Nor did she ever appear at Oscar ceremonies, even when she was nominated. Her aversion to publicity and the press was undeniably genuine, and exasperating to the studio at first. In an interview in 1928, she explained that her desire for privacy began when she was a child, stating, "As early as I can remember, I have wanted to be alone. I've always been moody. I detest crowds, I don't like many people." The artist James Montgomery Flagg said in 1933 that when he was allowed to sketch Garbo at a director's party in Hollywood some years earlier she told him she suffered from melancholia. At that time she had a Swedish phonograph record of laughs of all kinds which she played when visiting, to observe her hosts' response. In 1937, in a letter to her friend, Austrian actress and writer Salka Viertel, she wrote: "I go nowhere, see no one... It is hard and sad to be alone, but sometimes it's even more difficult to be with someone..." In another letter in 1970 she wrote: "I feel very tired and cannot seem to get myself together to plan where to go... I am sorry but something always seem to go a little wrong with me, and it is not in my head either..."

Although she was increasingly withdrawn in her final years, Garbo became close to her cook and housekeeper Claire Koger, who worked for her for 31 years. "We were very close—like sisters," Koger said.

Garbo never married, had no children, and lived alone for most of her adult life. Her most famous romance was with her frequent MGM co-star John Gilbert, with whom she lived intermittently in 1926 and 1927. Soon after their romance began, Gilbert began helping her develop acting skills on the set and teaching her how to behave like a star, socialize at parties, and deal with studio bosses. They co-starred again in three more hits: Love (1927), A Woman of Affairs (1928), and Queen Christina (1933). Gilbert allegedly proposed to Garbo numerous times and she finally accepted, but backed out just before the wedding. "I was in love with him," she said. "But I froze. I was afraid he would tell me what to do and boss me. I always wanted to be the boss." In later years when asked about Gilbert, Garbo said "I can't remember what I ever saw in him." According to Ava Gardner's autobiography, Garbo admitted to her that Gilbert was the only man she'd ever really loved but he had "let [her] down" by having a "superstitious affair" with "a little extra" during their last film and she had never forgiven him.

Garbo was an international movie star during the late silent era and the "Golden Age" of Hollywood who became a screen icon. For most of her career, Garbo was the highest-paid star at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, making her for many years the studio's "premier prestige star". After her death, the Los Angeles Times published an obituary calling her "the most alluring, vibrant and yet aloof character to grace the motion-picture screen." The April 1990 Washington Post obituary said that "at the peak of her popularity, she was a virtual cult figure."

American film director George Cukor: "She had a talent that few actresses or actors possess. In close-ups, she gave the impression, the illusion of great movement. She would move her head just a little bit, and the whole screen would come alive, like a strong breeze that made itself felt."

American film actress Kim Novak: "You know, my idol, I idolize Greta Garbo. I just loved her work so much. She was, again, so real. She was not -- to me, she wasn't stylized. You could see any of her work right now. She was just amazing, and what I loved about it also was there was an air of mystery about her work. There was always something more. She didn't give you everything. She held back, and I like that. I probably -- she was my role model."

Author Ernest Hemingway provided an imaginary portrayal of Garbo in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940): "Maybe it is like the dreams you have when someone you have seen in the cinema comes to your bed at night and is so kind and lovely ... He could remember Garbo still ... Maybe it was like those dreams the night before the attack on Pozoblanco, and [Garbo] was wearing a soft silky wool sweater when he put his arms around her, and when she leaned forward, and her hair swept forward and over his face, and she said why had he never told her that he loved her when she had loved him all this time? ... and it was as true as though it had happened ..."

Education

Garbo's formal education was limited due to her early involvement in acting. She attended school in Stockholm but focused more on developing her acting skills, which eventually led her to the stage and then to Hollywood.

In summary, Greta Garbo's life was a testament to her talent, financial savvy, and enduring legacy in Hollywood. Her net worth, while substantial, was a result of her successful career and shrewd investments, leaving behind a lasting impact on the world of cinema.

On 9 February 1951, she became a naturalized citizen of the United States, and bought a seven-room apartment at 450 East 52nd Street in Manhattan in 1953, where she lived for the rest of her life. Her New York apartment buzzer was identified by a solitary G and the interior was a "light and airy study in pink". In order to protect her privacy, she preferred being addressed as "Miss [Harriet] Brown". Her close friends were only allowed to call her Miss Garbo or G.G.; if they called her Greta, she wouldn't respond.

In 1971, Garbo vacationed in Southern France at the summer home of her close friend Baroness Cécile de Rothschild who introduced her to Samuel Adams Green, an art collector and curator in New York City. Green became an important friend and walking companion. He was in the habit of tape-recording all of his telephone calls, including many of his conversations with Garbo. He did so with her permission, but Garbo ended the friendship in 1981 after being falsely told that Green had played the tapes to friends. In his last will and testament, Green bequeathed all of the tapes in 2011 to the film archives at Wesleyan University. The tapes reveal Garbo's personality in later life, her sense of humor, and various eccentricities. In 1977, Garbo wrote to Frederick Sands: "I am forever running away from something or somebody"... "Unconsciously I have always known that I was not destined for real and lasting happiness."

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

* Sarris, Andrew. (1998). You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet: The American Talking Film – History and Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. New York. ISBN 0-19-513426-5