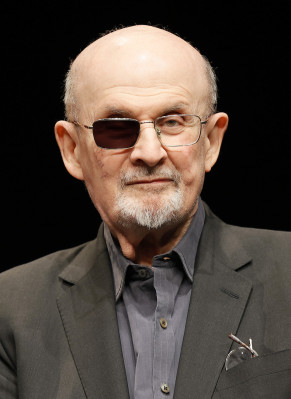

Age, Biography, and Wiki

Salman Rushdie was born in Mumbai, India, on June 19, 1947. He is best known for his novels that explore themes of identity, religion, and colonialism. Rushdie's work has been widely acclaimed, but it has also faced significant controversy, particularly with the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988, which sparked a global uproar and led to a fatwa against him.

| Occupation | Film Producer |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 19 June 1947 |

| Age | 78 Years |

| Birth Place | Bombay, British India |

| Horoscope | Gemini |

| Country | India |

Height, Weight & Measurements

There is no widely available specific information regarding Salman Rushdie's height, weight, or other physical measurements.

A former bodyguard to Rushdie, Ron Evans, planned to publish a book recounting the behaviour of the author during the time he was in hiding. Evans said Rushdie tried to profit financially from the fatwa and was suicidal, but Rushdie dismissed the book as a "bunch of lies" and took legal action against Evans, his co-author and their publisher. On 26 August 2008, Rushdie received an apology at the High Court in London from all three parties. A memoir of his years of hiding, Joseph Anton, was released on 18 September 2012; "Joseph Anton" was Rushdie's secret alias during the height of the controversy.

On 12 August 2022, while about to start a lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, New York, Rushdie was attacked by a man who rushed onto the stage and stabbed him repeatedly, including in the face, neck and abdomen. The attacker was pulled away before being taken into custody by a state trooper; Rushdie was airlifted to UPMC Hamot, a tertiary trauma centre in Erie, Pennsylvania, where he underwent surgery before being put on a ventilator.

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Body Measurements | |

| Eye Color | |

| Hair Color |

Dating & Relationship Status

Salman Rushdie has been married four times:

- Clarissa Luard (1976–1987)

- Marianne Wiggins (1988–1993)

- Elizabeth West (1997–2004)

- Padma Lakshmi (2004–2007)

He is the son of Anis Ahmed Rushdie, a Cambridge-educated lawyer-turned-businessman, and Negin Bhatt, a teacher. Rushdie's father was dismissed from the Indian Civil Services (ICS) after it emerged that the birth certificate submitted by him had changes to make him appear younger than he was. Rushdie has three sisters. He wrote in his memoir, Joseph Anton, that his father adopted the name Rushdie in honour of Averroes (Ibn Rushd). He recalls his "first literary influence": "When I first saw The Wizard of Oz it made a writer of me." He recalls "Every child in India in my day (and probably still) was obsessed with P. G. Wodehouse and Agatha Christie. I read mountains of books by both."

On 14 February 1989—Valentine's Day, and also the day of his close friend Bruce Chatwin's funeral—a fatwa ordering Rushdie's execution was proclaimed on Radio Tehran by Ayatollah Khomeini, the Supreme leader of Iran at the time, calling the book "blasphemous against Islam". Chapter IV of the book depicts the character of an Imam in exile who returns to incite revolt from the people of his country with no regard for their safety. According to Khomeini's son, his father never read the book. A bounty was offered for Rushdie's death, and he was thus forced to live under police protection for several years. On 7 March 1989, the United Kingdom and Iran broke diplomatic relations over the Rushdie controversy.

Rushdie has reported that he still receives a "sort of Valentine's card" from Iran each year on 14 February letting him know the country has not forgotten the vow to kill him and has jokingly referred to it as "my unfunny Valentine". He said, "It's reached the point where it's a piece of rhetoric rather than a real threat." Despite the threats on Rushdie personally, he said that his family has never been threatened, and that his mother, who lived in Pakistan during the later years of her life, even received outpourings of support. Rushdie himself has been prevented from entering Pakistan, however.

On 3 August 1989, while a man using the alias Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh was priming a book bomb loaded with RDX explosives in a hotel in Paddington, Central London, the bomb exploded prematurely, destroying two floors of the hotel and killing Mazeh. A previously unknown Lebanese group, the Organization of the Mujahidin of Islam, said he died preparing an attack "on the apostate Rushdie". There is a shrine in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery for Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh that says he was "Martyred in London, 3 August 1989. The first martyr to die on a mission to kill Salman Rushdie." Mazeh's mother was invited to relocate to Iran, and the Islamic World Movement of Martyrs' Commemoration built his shrine in the cemetery that holds thousands of Iranian soldiers slain in the Iran–Iraq War.

Rushdie has been married five times and has two children; his first four marriages ended in divorce. He was first married to Clarissa Luard, literature officer of the Arts Council of England, from 1976 to 1987. The couple had a son, Zafar, born in 1979, who is married to the London-based jazz singer Natalie Coyle. He left Clarissa Luard in the mid-1980s for the Australian writer Robyn Davidson, to whom he was introduced by their mutual friend Bruce Chatwin. Rushdie and Davidson never married, and they had split up by the time his divorce from Clarissa came through in 1987. Rushdie's second wife was the American novelist Marianne Wiggins; they were married in 1988 and divorced in 1993. His third wife, from 1997 to 2004, was British editor and author Elizabeth West; they have a son, Milan, born in 1997. After a miscarriage, the couple ended their relationship in 2004.

| Parents | |

| Husband | Clarissa Luard (m. 1976-1987) Marianne Wiggins (m. 1988-1993) Elizabeth West (m. 1997-2004) Padma Lakshmi (m. 2004-2007) Rachel Eliza Griffiths (m. 2021) |

| Sibling | |

| Children |

Net Worth and Salary

In 2025, Salman Rushdie's estimated net worth ranges from $10 million to $15 million. His wealth is primarily derived from book royalties, film rights, public speaking engagements, and academic fellowships.

Career, Business, and Investments

Rushdie's career is marked by several notable works:

- Midnight's Children (1981): This novel catapulted him to international fame, winning the Booker Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

- The Satanic Verses (1988): While controversial, it boosted his sales significantly, with estimated earnings of $2 million in the first two years.

- Other Works: Rushdie has published several novels, including Shame, The Moor's Last Sigh, and The Enchantress of Florence.

Rushdie was the President of PEN American Center from 2004 to 2006 and founder of the PEN World Voices Festival. In 2007, he began a five-year term as Distinguished Writer in Residence at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, where he has also deposited his archives. In May 2008, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2014, he taught a seminar on British Literature and served as the 2015 keynote speaker In September 2015, he joined the New York University Journalism Faculty as a Distinguished Writer in Residence.

Though he enjoys writing, Rushdie says he would have become an actor if his writing career had not been successful. From early childhood, he dreamed of appearing in Hollywood films (which he later realised in his frequent cameo appearances).

Rushdie announced in June 2011 that he had written the first draft of a script for a new television series for the US cable network Showtime, a project on which he will also serve as an executive producer. The new series, to be called The Next People, will be, according to Rushdie, "a sort of paranoid science-fiction series, people disappearing and being replaced by other people." The idea of a television series was suggested by his US agents, said Rushdie, who felt that television would allow him more creative control than feature film. The Next People is being made by the British film production company Working Title, the firm behind projects including Four Weddings and a Funeral and Shaun of the Dead.

In 2004, very shortly after his third divorce, Rushdie married Padma Lakshmi, an Indian-born actress, model, television personality, producer, author, businessperson, and activist. At the time of their first meeting in 1999, Lakshmi was 28, while Rushdie was 51. Rushdie stated that Lakshmi had asked for a divorce in January 2007, and later that year, in July, the couple filed it. Padma Lakshmi criticized Rushdie as insecure and spoiled, stating he constantly craved praise and demanded "frequent sex." Rushdie derided her, calling her a "bad investment." Lakshmi also said that Rushdie was insensitive to her painful endometriosis.

Social Network

Salman Rushdie maintains a presence on social media platforms, though specific follower counts are not readily available. His public life is often reflected in his writings and public appearances.

He also recalls that "Alice captured my imagination as few other books did: both the books, not just Alice's Adventures in Wonderland but Through the Looking-Glass as well, and I can still recite the whole of "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter" from memory. I also loved the Swallows and Amazons series by Arthur Ransome because of the unimaginable freedom those young people sailing in the Lake District were given by their families ... When I was 16, I read The Lord Of The Rings and became obsessed, and can still recite the inscription on the Ruling Ring ('One ring to rule them all...') in the dark language of Mordor. I read an astonishing amount of Golden Age science fiction, not just Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke and Kurt Vonnegut but more arcane writers like Clifford D. Simak, James Blish, Zenna Henderson and L. Sprague de Camp." He has written about his family following the Indian custom of kissing holy books if they were dropped on the floor. "But we kissed everything. We kissed dictionaries and atlases. We kissed Enid Blyton novels and Superman comics. If I'd ever dropped the telephone directory I'd probably have kissed that, too."

Rushdie’s works are often categorized as postmodern, particularly within the tradition of Magic Realism. However, they also reveal early signs of a literary and cultural shift beyond postmodernism. In our contemporary world – saturated with reality TV, talk shows and other forms of pure entertainment – apathy, passivity and inaction have become defining features. Jeffrey T. Nealon identifies this prevailing sense of disengagement as a hallmark of the post-postmodern condition, which is sometimes referred to as metamodernism: “we post-postmodern capitalists are trained by our media masters to watch rather than act, consume rather than do.” The overt political tensions of the Cold War era have been replaced by a more insidious, media-driven culture of distraction and spectacle. In response, Rushdie's works blend fantasy with realism to jolt readers out of this stupor, challenging delusions and encouraging renewed critical awareness.

Rushdie's debut, the science fiction tale Grimus (1975), was generally ignored by the public and literary critics. His next novel, Midnight's Children (1981), put him on the map. It follows the life of Saleem Sinai, born at the stroke of midnight as India gained its independence, who is endowed with special powers and a connection to other children born at the birth of the modern nation of India. Sinai has been compared to Rushdie. However, Rushdie refuted the idea of having written any of his characters as autobiographical, stating, "People assume that because certain things in the character are drawn from your own experience, it just becomes you. In that sense, I've never felt that I've written an autobiographical character." Rushdie writes of his "debt to the oral narrative traditions of India and also to the great novelists Jane Austen and Charles Dickens—Austen for her portraits of brilliant women caged by the social convention of their time, women whose Indian counterparts I knew well; Dickens for his great, rotting, Bombay-like city, and his ability to root his larger-than-life characters and surrealist imagery in a sharply observed, almost hyperrealistic background."

Shortly after its publication, V. S. Pritchett wrote: "In Salman Rushdie, the author of Midnight's Children, India has produced a glittering novelist—one with startling imaginative and intellectual resources, a master of perpetual storytelling. Like García Marquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude, he weaves a whole people's capacity for carrying its inherited myths—and new ones that it goes on generating—into a kind of magic carpet. The human swarm swarms in every man and woman as they make their bid for life and vanish into the passion or hallucination that hangs about them like the smell of India itself. Yet at the same time there are strange Western echoes, of the irony of Sterne in Tristram Shandy—that early nonlinear writer—in Rushdie's readiness to tease by breaking off or digressing at the gravest moments. This is very odd in an Indian novel! The book is really about the mystery of being born and the puzzle of who one is." Midnight's Children won the 1981 Booker Prize and, in 1993 and 2008, the Best of the Bookers and Booker of Bookers special prizes.

His most controversial work, The Satanic Verses, was published in 1988 and won the Whitbread Award. It was followed by Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990). Written in the shadow of the fatwa, it is about the magic of story-telling and an allegorical defence of the power of stories over silence.

In 1990, Rushdie reviewed Thomas Pynchon's Vineland in The New York Times, and offered some droll musings on the author's reclusiveness: "So he wants a private life and no photographs and nobody to know his home address. I can dig it, I can relate to that (but, like, he should try it when it's compulsory instead of a free-choice option)." Rushdie recalls: "I was able to meet the famously invisible man. I had dinner with him at Sonny Mehta's apartment in Manhattan and found him very satisfyingly Pynchonesque. At the end of dinner I thought, well, now we're friends, and maybe we'll see each other from time to time. He never called again."

Following Fury (2001), set mainly in New York and avoiding the previous sprawling narrative style that spans generations, periods and places, Rushdie's novel Shalimar the Clown (2005), a story about love and betrayal set in Kashmir and Los Angeles, was hailed as a return to form by a number of critics.

2008 saw the publication of The Enchantress of Florence, one of Rushdie's most challenging works that focuses on the past. It tells the story of a European's visit to Akbar's court, and his revelation that he is a lost relative of the Mughal emperor. The novel was praised by Ursula Le Guin in a review in The Guardian as a "sumptuous mixture of history with fable". Luka and the Fire of Life, a sequel to Haroun and the Sea of Stories, was published in November 2010 to critical acclaim. Earlier that year, he announced that he was writing his memoir, Joseph Anton: A Memoir, which was published in September 2012.

In 2012, Rushdie became one of the first major authors to embrace Booktrack (a company that synchronises ebooks with customised soundtracks), when he published his short story "In the South" on the platform.

2015 saw the publication of Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, a modern take on the One Thousand and One Nights. Based on the conflict of scholar Ibn Rushd (from whom Rushdie's family name derives), Rushdie explores themes of transnationalism and cosmopolitanism by depicting a war of the universe with a supernatural world of jinns. Ursula K. Le Guin wrote: "Rushdie is our Scheherazade, inexhaustibly enfolding story within story and unfolding tale after tale with such irrepressible delight that it comes as a shock to remember that, like her, he has lived the life of a storyteller in immediate peril. Scheherazade told her 1,001 tales to put off a stupid, cruel threat of death; Rushdie found himself under similar threat for telling an unwelcome tale. So far, like her, he has succeeded in escaping. May he continue to do so."

In 1989, The New York Times published "Words For Salman Rushdie": "28 distinguished writers born in 21 countries speak to him from their common land – the country of literature. For expressing their ideas publicly in the past many of these writers have suffered censorship, exile – forced or self-imposed – and imprisonment." Czesław Miłosz wrote: "I have particular reasons to defend your rights, Mr. Rushdie. My books have been forbidden in many countries or have had whole passages censored out. I'm grateful to people who stood then by the principle of free expression, and I back you now in my turn." Ralph Ellison: "You deserve the full and passionate solidarity of any man of dignity, but I am afraid this is too little. This story of a man alone against worldwide intolerance, and of a book alone against the craziness of the media, can become the story of many others. The bell tolls for all of us." Umberto Eco: "Keep to your convictions. Try to protect yourself. A death sentence is a rather harsh review." Anita Desai: "Silence, exile and cunning, yes. And courage."

Christopher Hitchens recalled: "When the Washington Post telephoned me on Valentine's Day 1989 to ask for my opinion about the Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwah, I felt at once here was something that completely committed me. It was, if I can phrase it like this, a matter of everything I hated versus everything I loved. In the hate column: dictatorship, religion, stupidity, demagogy, censorship, bullying, and intimidation. In the love column: literature, irony, humour, the individual, and the defense of free expression. Plus, of course, friendship–although I'd like to think my response would have been the same even if I hadn't known Salman at all. To re-state the premise of the argument again: the theocratic head of a foreign despotism offers money in his own name in order to suborn the murder of a civilian of another country, for the offense of writing a work of fiction. No more root-and-branch challenge to the values of the Enlightenment (on the bicentennial of the fall of the Bastille), or to the First Amendment to the Constitution, could be imagined." Rushdie wrote: "I have often been asked if Christopher defended me because he was my close friend. The truth is that he became my close friend because he wanted to defend me ... He and I found ourselves describing our ideas, without conferring, in almost identical terms. I began to understand that while I had not chosen the battle it was at least the right battle, because in it everything that I loved and valued (literature, freedom, irreverence, freedom, irreligion, freedom) was ranged against everything I detested (fanaticism, violence, bigotry, humorlessness, philistinism, and the new offense culture of the age). Then I read Christopher using exactly the same everything-he-loved-versus-everything-he-hated trope, and felt … understood."

In 1990, soon after the publication of The Satanic Verses, a Pakistani film entitled International Gorillay (International Guerillas) was released that depicted Rushdie as a "James Bond-style villain" plotting to cause the downfall of Pakistan by opening a chain of casinos and discos in the country; he is ultimately killed at the end of the movie. The film was popular with Pakistani audiences, and it "presents Rushdie as a Rambo-like figure pursued by four Pakistani guerrillas". The British Board of Film Classification refused to allow it a certificate; "it was felt that the portrayal of Rushdie might qualify as criminal libel, causing a breach of the peace as opposed to merely tarnishing his reputation." This effectively prevented the release of the film in the UK. Two months later, however, Rushdie himself wrote to the board, saying that while he thought the film "a distorted, incompetent piece of trash", he would not sue if it were released. He later said, "If that film had been banned, it would have become the hottest video in town: everyone would have seen it". While the film was a great hit in Pakistan, it went virtually unnoticed elsewhere.

Rushdie advocates the application of higher criticism, pioneered during the late 19th century. In a guest opinion piece printed in The Washington Post and The Times in mid-August 2005, Rushdie called for a reform in Islam.

"We need all of us, whatever our background, to constantly examine the stories inside which and with which we live. We all live in stories, so called grand narratives. Nation is a story. Family is a story. Religion is a story. Community is a story. We all live within and with these narratives. And it seems to me that a definition of any living vibrant society is that you constantly question those stories. That you constantly argue about the stories. In fact the arguing never stops. The argument itself is freedom. It's not that you come to a conclusion about it. And through that argument you change your mind sometimes.… And that's how societies grow. When you can't retell for yourself the stories of your life then you live in a prison.… Somebody else controls the story.… Now it seems to me that we have to say that a problem in contemporary Islam is the inability to re-examine the ground narrative of the religion.… The fact that in Islam it is very difficult to do this, makes it difficult to think new thoughts."

Rushdie is an advocate of religious satire. He condemned the Charlie Hebdo shooting and defended comedic criticism of religions in a comment originally posted on English PEN where he called religions a medieval form of unreason. Rushdie called the attack a consequence of "religious totalitarianism", which according to him had caused "a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam". He said:

"Religion, a medieval form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today. I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. 'Respect for religion' has become a code phrase meaning 'fear of religion.' Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect."

When asked about reading and writing as a human right, Rushdie states: "...there are the larger stories, the grand narratives that we live in, which are things like nation, and family, and clan, and so on. Those stories are considered to be treated reverentially. They need to be part of the way in which we conduct the discourse of our lives and to prevent people from doing something very damaging to human nature." Though Rushdie believes the freedoms of literature to be universal, the bulk of his fictions portrays the struggles of the marginally underrepresented. This can be seen in his portrayal of the role of women in his novel Shame. In this novel, Rushdie, "suggests that it is women who suffer most from the injustices of the Pakistani social order." His support of feminism can also be seen in a 2015 interview with New York magazine's The Cut.

In the wake of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy in March 2006 Rushdie signed the manifesto Together Facing the New Totalitarianism, a statement warning of the dangers of religious extremism. The Manifesto was published in the left-leaning French weekly Charlie Hebdo in March 2006. When Amnesty International suspended human rights activist Gita Sahgal for saying to the press that she thought the organization should distance itself from Moazzam Begg and his organization, Rushdie said: "Amnesty…has done its reputation incalculable damage by allying itself with Moazzam Begg and his group Cageprisoners, and holding them up as human rights advocates. It looks very much as if Amnesty's leadership is suffering from a kind of moral bankruptcy, and has lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong. It has greatly compounded its error by suspending the redoubtable Gita Sahgal for the crime of going public with her concerns. Gita Sahgal is a woman of immense integrity and distinction. ... It is people like Gita Sahgal who are the true voices of the human rights movement; Amnesty and Begg have revealed, by their statements and actions, that they deserve our contempt."

In May 2024, Rushdie argued that if a Palestinian state ever came into being, it would resemble a "Taliban-like state" and become a client state of Iran. He further stated, "There's an emotional reaction to the death in Gaza, and that's absolutely right. But when it slides over towards antisemitism and sometimes to actual support of Hamas, then it's very problematic." He voiced his puzzlement regarding the current support of progressive students for what he described as a "fascist terrorist group".

Rushdie has expressed his preference for India over Pakistan on numerous occasions in writing and on live television interviews. In one such interview in 2003, Rushdie said "Pakistan sucks" after being asked about why he felt more like an outsider there than in India or England. He cited India's diversity, openness, and "richness of life experience" as his preference over Pakistan's "airlessness", resulting from a lack of personal freedom, widespread public corruption, and inter-ethnic tension.

Education

Rushdie was educated at Cathedral and John Connon School in Mumbai and later attended Rugby School in England. He graduated from King's College, Cambridge, with a degree in History.

In 1983, Rushdie was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He was appointed a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of France in 1999. Rushdie was knighted in 2007 for his services to literature. In 2008, The Times ranked him 13th on its list of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945. Since 2000, Rushdie has lived in the United States. He was named Distinguished Writer in Residence at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute of New York University in 2015. Earlier, he taught at Emory University. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2012, he published Joseph Anton: A Memoir, an account of his life in the wake of the events following The Satanic Verses. Rushdie was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in April 2023.

Rushdie grew up in Bombay and was educated at the Cathedral and John Connon School in Fort in South Bombay, before moving to England in 1964 to attend Rugby School in Rugby, Warwickshire. He then attended the University of Cambridge as an undergraduate student at King's College, Cambridge, from where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in History.

In 2017, The Golden House, a satirical novel set in contemporary America, was published. 2019 saw the publication of Quichotte, a modern retelling of Don Quixote. In 2021 Languages of Truth, a collection of essays written between 2003 and 2020, was published. Rushdie's fifteenth novel Victory City, described as an epic tale of a woman who breathes a fantastical empire into existence, was published in February 2023. The book was Rushdie's first released work after he was attacked and severely injured as he was about to give a public lecture in New York in 2022. In April 2024, his autobiographical book Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, in which Rushdie writes about the attack and his recovery, was published. It was longlisted for the 2024 National Book Award for Nonfiction.

Rushdie is a member of the advisory board of The Lunchbox Fund, a non-profit organisation that provides daily meals to students of township schools in Soweto of South Africa. He is a member of the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America, an advocacy group representing the interests of atheistic and humanistic Americans in Washington, D.C., and a patron of Humanists UK (formerly the British Humanist Association). He is a laureate of the International Academy of Humanism. In November 2010 he became a founding patron of Ralston College, a new liberal arts college that has adopted as its motto a Latin translation of a phrase ("free speech is life itself") from an address he gave at Columbia University in 1991 to mark the 200th anniversary of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

In 1989, in an interview following the fatwa, Rushdie said that he was in a sense a lapsed Muslim, though "shaped by Muslim culture more than any other," and a student of Islam. In another interview the same year, he said, "My point of view is that of a secular human being. I do not believe in supernatural entities, whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim or Hindu."

"What is needed is a move beyond tradition, nothing less than a reform movement to bring the core concepts of Islam into the modern age, a Muslim Reformation to combat not only the jihadist ideologues but also the dusty, stifling seminaries of the traditionalists, throwing open the windows to let in much-needed fresh air. ... It is high time, for starters, that Muslims were able to study the revelation of their religion as an event inside history, not supernaturally above it. ... Broad-mindedness is related to tolerance; open-mindedness is the sibling of peace."